The Moment Grasshopper Finally Made Sense to Me

It's like I woke up with a new pair of eyes

This article is part of the Designing with Numbers series, a continuation of the Geometry Basics series. Together, they explore how computational design is shaped first by geometry, then by numbers.

Part 1 : It’s not always about geometry, numbers matter too.

Part 2 : How Curve Parameters Give You More Control in Grasshopper

Part 3 : How Surface Parameters Turn Geometry Into Information

Part 5 : Using Logic to Guide Your Models in Computational Design

Part 7 : The Moment Grasshopper Finally Made Sense to Me (This article)

I’m not exactly sure when it “clicked” for me, but I know it was sometime around three years ago.

It was a hot, sunny day. I could feel myself starting to sweat as I seek refuge in the office on the hill. Why are all the good lunch spots on the bottom of the hill? Better yet, why is the office so far up this hill?

All good questions.

When I got back to my desk, I found myself just staring at my Grasshopper script. My brain was cooling off from the heat outside. Thank whoever made air-conditioning. Or maybe I had too much for lunch. I knew ordering extra fries was a bad idea.

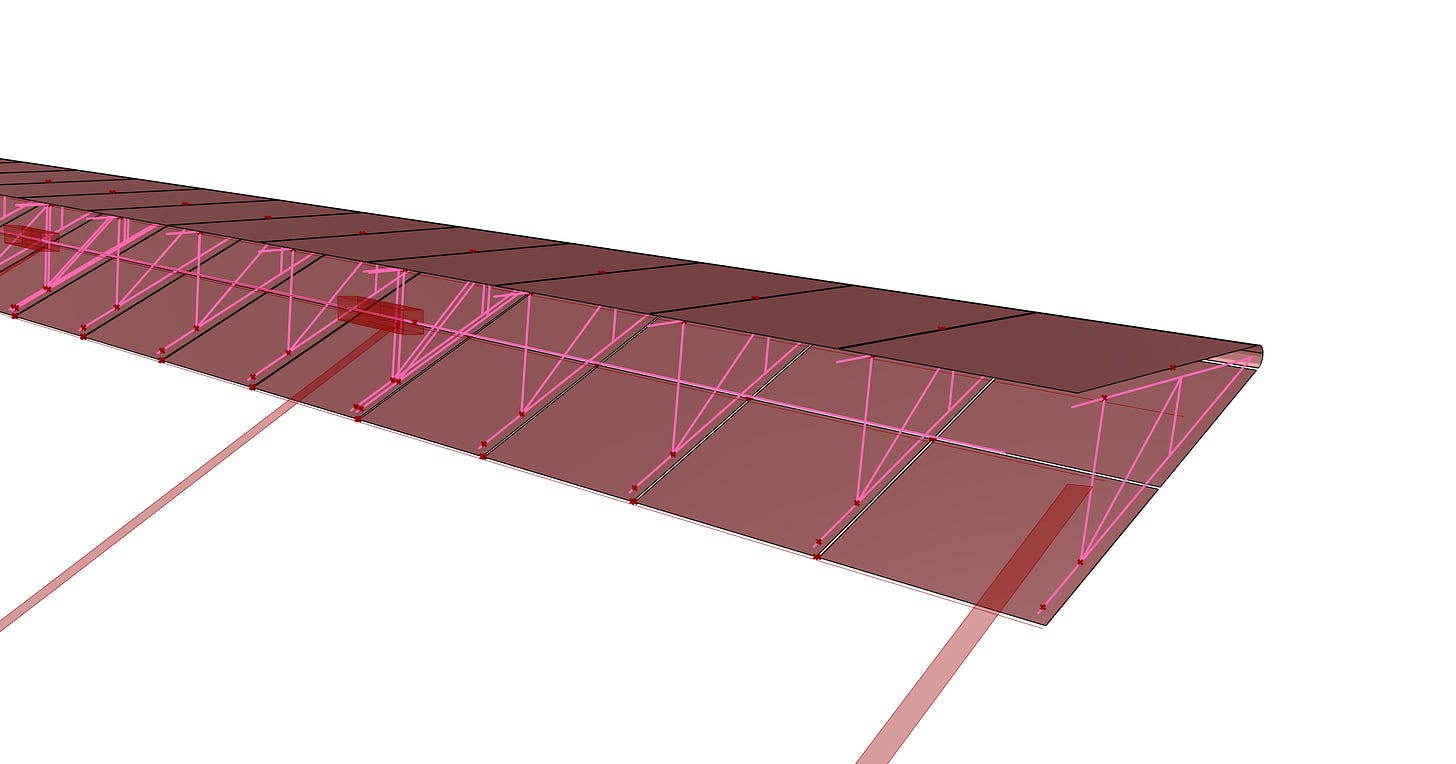

I was putting the finishing touches on a part of a huge complicated roof that our team had been working on. It was called the “bullnose” and this is the 12th iteration of the script.

As I sat there, in my food coma state, I noticed how many moving pieces were working together to get this model out.

We start with the reference curves given by the architects. They help us set out the geometry but they are too smooth. So I had to rationalize them into “constructible modules”. That was majority of the script actually, it was turning a completely smooth curve into construction ready geometry accounting for all the real life parameters (like which panels could be opened, where the fire sprinklers go, etc)

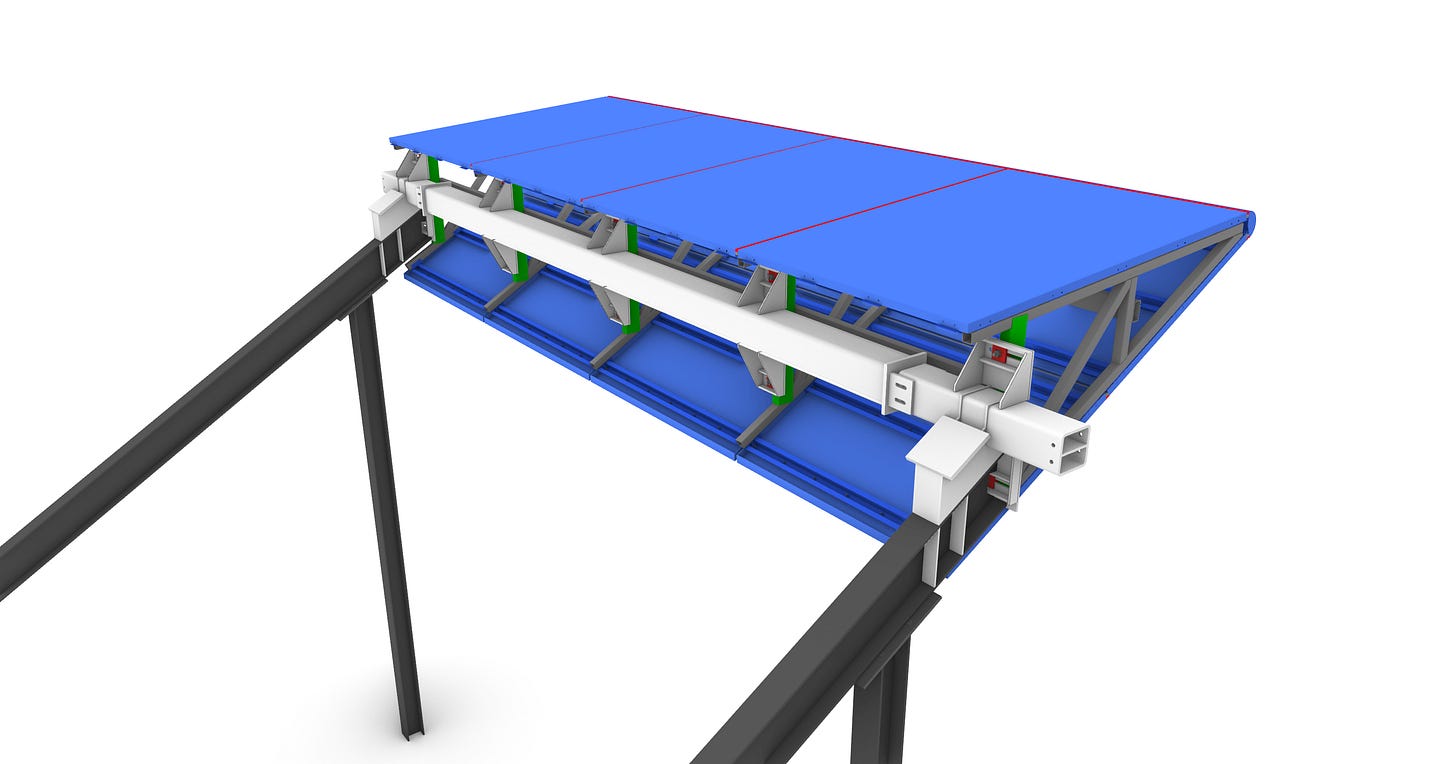

Then, there was the structural design part to all of this. Not only do we have to give a highly detailed 3D model in the end, we also had to ensure that it held up structurally.

While the script didn’t handle the analysis, it had to assign the right member sizes (whether it was an I-beam, a tube, a hollow rectangle, etc) to the right modules based on the location of the roof as the wind and rain loads were unique to different sections of the roof.

Once, the geometry created and the right member sizes assigned, the script now had to push everything into Revit. Taking into account the various offsets for the connections and other important metadata. Of the 100s, the most important one was the module number because that is what the client was using to delegate which section of the roof gets built first.

In the end, after combining all these parts. Wenget a highly detailed model that went from a few reference curves, all the way to fully designed and constructible modules.

And that was just one part of the roof. Through out the rest of the year, we worked on doing the same thing but for all the other parts.

As I slowly came back from the food coma, it hit me how amazing that all of this worked together. Here was a program (Rhino) originally build for modeling but is now being used to process and transfer all this information across disciplines. It pulled together a whole bunch of data and geometry to somehow create this model.

It’s why I think of Grasshopper as a platform instead of just a tool. It can pull together all the information from disparate places, process it and transform it in a way that’s useful to you and the project.

It wasn’t always like this

Thinking back, even though I knew how to write code, I was not a good Grasshopper user. Writing code and Grasshopper scripts may share similarities, but you need a different mindset for each one.

I fought every hard problem with more “programming” logic instead of trying to learn how Grasshopper wanted to work. I’d dig through forums for obscure plugins, use unnecessary components, and write loops just to make something work. Because those were the ways I solved problems in programming.

The truth is, I tried to force my own habits onto Grasshopper. I didn’t want to deal with data trees or understand how to think geometrically, I just wanted to get results.

And part of the problem is that Grasshopper let’s me. It’s what makes it so appealing. You can approach it from almost any angle, and somehow, it’ll run. You might even find plugins (like the looping plugin) that encourages your approach.

But even though Grasshopper let’s you, it doesn’t mean you should. Because you’re going against it’s deign intent. It means you’ll always be fighting Grasshopper instead of working with it. it’s a kind of false hope.

The turning point

It wasn’t until working on this roof that it clicked for me. That I understood the “Grasshopper” way which is still hard to articulate. As woo woo as it sounds, I think it’s something you have to discover for yourself by doing the same thing I did. Force your own way through, realized all the mistakes and then repeat it until you understand what Grasshopper can and can’t do.

This roof project pushed me to understand that it’s way more productive to work with the tool than against it. I started understanding what it meant to have a “clean” script, to use vectors and data-trees or even to use meshes because it’s more performant than using Breps everywhere.

The more I understood what I was working with, the more freedom it gave me.

Designing with numbers

That, really, is what this whole Designing with Numbers series has been about:

Understanding what we’re actually working with inside Grasshopper.

By understanding more, we start to see geometry as layers of information. And knowing how to prod, wrangle and extract information at different layers while respecting the “rules” of Grasshopper, is what let’s you solve problems your own way

It’s a kind of freedom through understanding but still constrained to the rules.

The more you learn about how things work, the more creative control you gain. It’s like painting, at first you’ll find the canvas restrictive because it’s not like drawing, but over time once you learn and understand the “rules” of painting, you can start to play and experiment with different ways of expressing yourself.

This series was never meant to be a tutorial. It’s been a reflection on the principles that shape how I use Grasshopper or any computational tool for that matter.

But if you’re just starting out and brute-forcing your way through scripts, that’s still okay. My way isn’t the perfect or even the correct way. Maybe throughout this series, I have inspired you to see what I mean when I say geometry is data.

And once that clicks, it may wake you from brute-force stupor as it did for me.

Final Thoughts

So this article marks the end of the Designing with Numbers series, at least for now.

If I come across something new that belongs here, I’ll add to it.

Writing these pieces has been my way of making sense of the more abstract parts of computational design. It’s the thoughts that often sit in my head but rarely get communicated to anyone else. They are too abstract and disparate to be made into a course and I wanted to use the process of writing to thoroughly understand how I think about these concepts.

If you’ve followed along from the beginning, thank you for taking the time to read, think, and explore with me.

Until next time,

Stay curious

Want to learn where to apply computational design?

Subscribe to CodedShapes and I’ll send you my free guide on how to actually do that