We Need to Stop Asking LLMs to Do Everything at Once (For Now)

It just can't do that many things at once

Yes, yes I know, it’s another AI article.

I’ve deliberately avoided writing about AI for as long as possible. There are so many articles, videos and opinions about AI out there now that I didn’t want to just add to the noise.

But what changed my mind was seeing Rob Asher (CEO of Giraffe) talk about how he thinks about AI at the last CEGS meetup (btw, if you’re in Sydney, you should totally come).

Rob’s articulation of using AI gave me the language to explain how I’ve been thinking and using these LLMs. It’s probably why I’ve put off writing about it for so long.

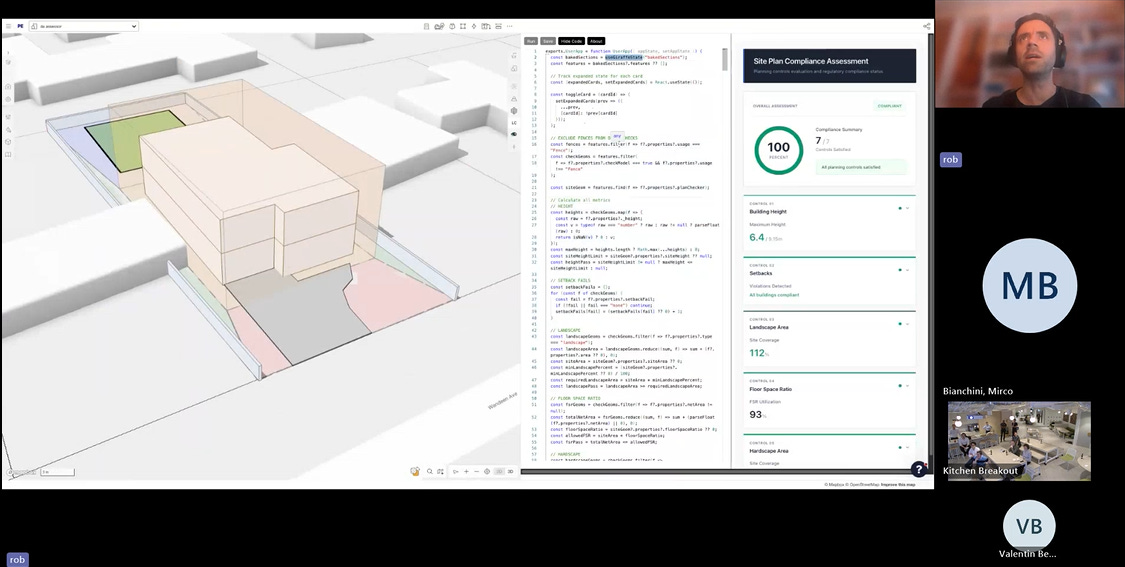

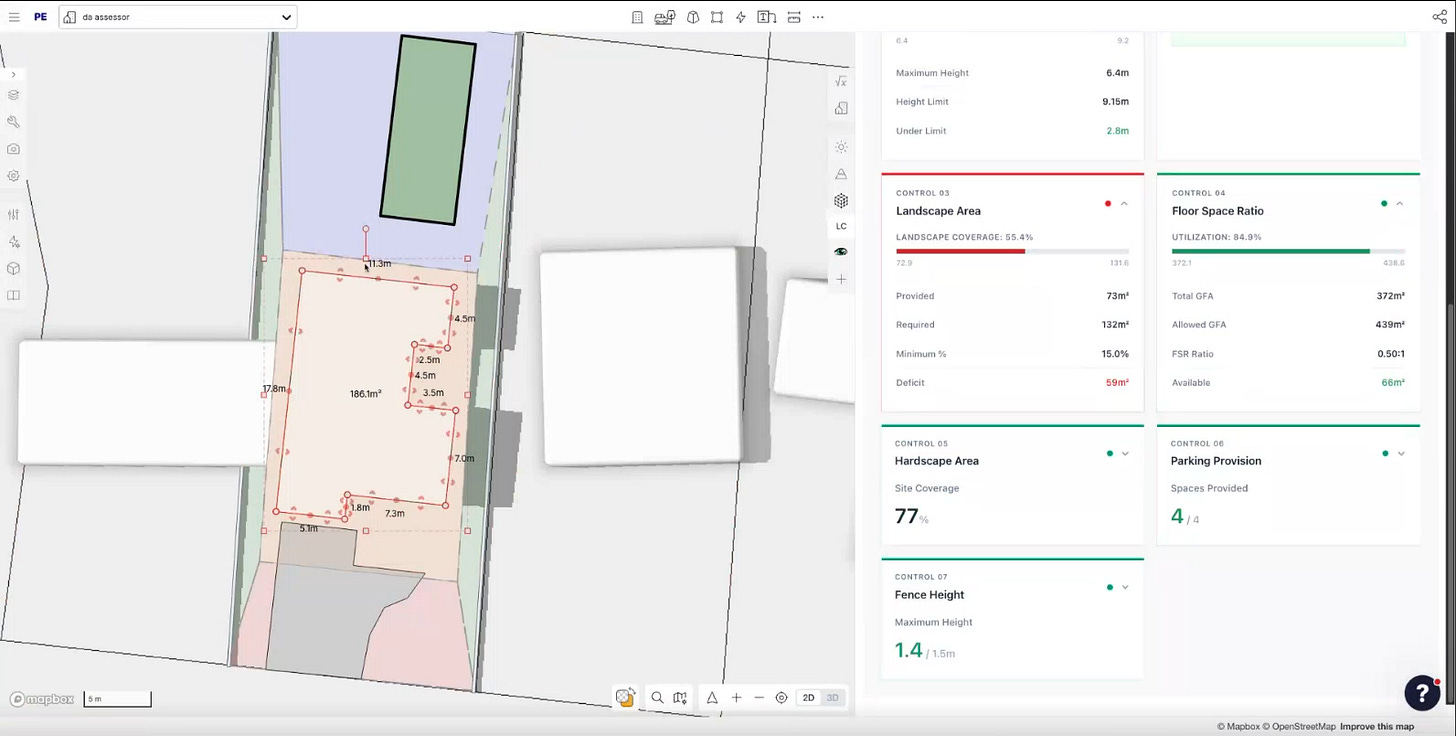

Btw, if you don’t know Rob, he’s the CEO of Giraffe, which is this amazing urban planning and modelling tool on the web. It’s got some AI baked into it as well as a lot of other cool things

Rob basically took us through how he thought about AI and how he’s integrated it into Giraffe.

And what stuck with me was the principle of

Limits and Intentionality

Not only does it apply to LLMs, but it also applies to computational design.

So, I’m hoping this article shares that mindset with you. I know it’s not a prompting guide. It’s not about how to use agents. Or which chatbot is the best.

But I think having the right mindset about LLMs can greatly improve the way you work with them. It’s not the “best” or only way. In fact, this entire article might be irrelevant if LLMs get super good.

But, for now I’ve found great results with this approach and I’d like to share it.

What Limits and Intentionality Actually Means

From my experience (and again, with AI it’s not as extensive as some others out there), I’ve found the best results come from limiting what LLMs have to do and what they have access to. Generally, this means you have to be pretty intentional with what you want.

Even Anthropic’s own prompting guides emphasize being “clear and direct” with your instructions. Their guidance is “Think of Claude like a smart but new employee who has no context on what to do aside from what you explicitly tell them.”

By being more specific, you limit the possible answers (the solution space) that any of these LLMs can give you. When the solution space is too large, you get generic results. By being more specific, you place constraints on the answers or tools that the LLMs can use, giving you much better results.

And we’ve seen this challenge evolve as LLMs try to maintain context across conversations. Claude has Projects and Memory features, ChatGPT has its memory system. Both attempting to “remember” your preferences, so you don’t have to repeat yourself.

But even with these features, you can’t just dump thousands of documents and ask it “write like me” because the solution space is still too large. Just having memory enabled doesn’t mean ChatGPT suddenly writes in your voice. I can’t count how many times I’ve said “use all the previous context to write in my voice” only to get something that still sounds too AI-ey. The memory is there, but without clear, limited instructions about how to use that memory, you still get generic output.

It’s actually what I see with computational design too. With Grasshopper or programming, you can solve almost anything you want. But it’s really about understanding where to best put that effort. Similar with LLMs, we all just need some help narrowing down the list of possible answers.

So, that means whether it’s computational design or LLM, you still need to start with understanding what you’re actually solving first. I know it sounds woo woo to say this, but if your intention is muddy, your results from any process will also be muddy.

In their guide on effective context engineering, Anthropic describes this balance as finding “the right altitude”. It’s to give instructions that specific enough to guide behavior effectively, yet flexible enough to let the model use its strengths. At one extreme, you get brittle, over-constrained prompts. At the other, vague guidance that assumes too much shared context.

Funnily enough, it’s actually how I wish most teams would tell me their problem. Give me enough context to guide the outcome but also the flexibility to let me make the computational design decisions. Learning how to prompt these LLMs has actually taught me how to tell teams to give me information too.

Am I a LLM of computational design ?

But whether you’re talking to me or an LLM, the idea is the same. Narrow the scope, be specific about your intent, and LLMs (or me) perform remarkably well. Give them the entire universe to work with, and you get mediocre generalities.

“The smaller the ask, the more prescriptive, the better... Limits. That’s what I would recommend... my theme would be limits. Limits are very useful.” - Rob Asher

Okay, but what would this article be without some personal examples?

I’ll start with how I use it in computational design and then we’ll move on to more general “operational” type things.

Note: There are so many ways to use LLMs, this is just how I use it. If you have ideas on how I can improve, please let me know in the comments or email!

Using Claude Code to Process and Visualise Data

The one thing I use Claude Code (or any kind of desktop LLM) is for anything that Python can do.

These past few weeks, a lot of my work has been geometrical and visual. What this means is that I’m generating a bunch of geometry or analyzing some results and then turning that into a visual format for clients. That would mean creating models and then taking screenshots and arranging them on a PDF. Or it would be taking the results of an analysis model and then turning that into graphs for clients.

A lot of that work is handled by Python. Pre-LLM, I had “template” scripts that helped me with this. I would copy a script from an existing project, then tweak it to match the graphics for the current one. Do that enough times, and you tend to build up a “library” of Python scripts that generate a bunch of different visuals for you.

But there’s still so much manual tweaking to do. Where to put the legend, what the x or y labels look like, etc. These were things that were tedious to do. You had to remember the syntax and the functions to edit them.

Well, now LLMs are great with that kind of stuff. And if you constrain all those options, it’s amazing at returning the exact visual. Most of the time, if you can specify in text the exact solution you want together with the exact tools to use, it will write the code for you. And most of the time, it will get it right in the first go.

This is limits and intentionality in action. Instead of asking for something vague, I’m constraining the toolset (use Matplotlib), the data source (specific CSV columns), and the output (specific graph type). The LLM doesn’t have to guess what I want, it has clear boundaries and tools to work with.

It’s the difference between:

“Give me a graph that shows the deflections”

VS

“Use Matplotlib and plot vertical deflection graphs. Use the columns ‘Relative deflection’ and ‘stages’ in the CSV that you can find in the folder for this. Then plot them vertically stacked and ensure that all graphs have the same y limits.”

Use Claude’s /plan Feature to Execute More Complex but Specific Actions

With Claude’s new /plan feature, you can actually execute more complex tasks in chunks rather than describing it in one complex prompt.

If you know how to exactly describe the output you want, you can try specifying that that step-by-step. Kinda how you would tell an intern to work.

This aligns with what Anthropic calls chain of thought prompting, breaking down complex tasks into steps dramatically improves performance. It means if you can describe your intention clearly and limit the types of steps that the LLM has to use, you get much better results.

It’s actually the reason I think LLMs don’t work well with geometry, because there’s not inherently good way to describe geometry. Rob also made this point in his talk at CEGS.

“The drawing is still more efficient than text like I can draw faster than I can talk... just try and describe this to yourself as a text document. I think the geometry is innately interesting and a picture tells 1000 words.”

That’s why I would still use Grasshopper or some computational tool for any geometrical or procedural process but process any text based task (code, data, etc) with LLMs. I have found that I get the best of both worlds by doing so.

Using LLMs to Edit Text

Okay, no doubt you have seen the amount of AI generated articles and text on the internet now and since I write, it makes sense to rely on LLMs more.

But as tempting as it is, I try not to use LLMs to generate any kind of text for the articles I write. And again, this circle backs to limits, asking an LLM to “write me an article about computational design” is way too vague and the solution space is too broad.

P.S. I might be wrong about this in the future, if LLMs get ridiculously good

As many prompts or techniques as I’ve found, LLMs are just not good at generating articles the way I want them to. Everything still sounds too AI-ey.

What I think LLMs are better at is editing. It doesn’t take the pain of writing that first draft away, but editing with LLMs helps me hone in on the point I’m trying to make. Even then, it still sometimes make some of my sentences too AI-ey (Not because of X, but Y sound familiar ?)

Limits here help the LLM, because it has my draft to work with, it knows to use it to infer tone, context and style. But I still find it horrible at editing an entire article.

To counter that, I still only feed in a paragraph at a time along with some specific prompting to get it to produce good results. But even then, it might still be a hit or miss, especially if I’m going for a more conversational tone or being satirical. It doesn’t seem to understand that well, or it goes overboard with it.

1-2 paragraphs at a time seems to be the sweet spot for me. I’ll also sometimes feed it any existing paragraphs (in the same message) or the outline of the article, so the LLM knows the type of tone/style I’m aiming for.

It basically comes back to limits and intentionality again. Instead of “edit this article,” I constrain it to “edit this paragraph based on this outline and use the previous paragraph as context for the tone.”

And even though people have recommended adding previous articles into its context, I haven’t found much luck with that. I think even with only my previous articles, the solution space is too vast.

Using LLMs for smart search

Another way I use LLMs is to “smart” search for things. That could be research on the internet or just looking through a whole heap of PDFs.

It’s been useful, but again, it only works well when I narrow down the landscape.

Telling it “Do some research, find me a good way of using AI that I can use in my article” is still too broad.

I have found better results with:

“I’m trying to write this article about AI. [insert article] I want my angle to be about mindset. So can you do some research on the internet for people talking about principles with AI, not just guides. Avoid tutorials or any step-by-step articles.”

I’m being intentional in telling the LLM what I’m looking for (principles, not tutorials), what to avoid (step-by-step guides), and what context matters (mindset-focused). The search space is constrained.

Because the internet is a big place, giving it the context of what I’m looking for helps. This is where I have found MCPs to be helpful. Generally because they limit the amount of options Claude has to work with and they work on top of already refined and filtered options.

Things like Firecrawl or Apify really help with getting better search results from the internet. It may take longer and cost more credits, but the results are always better.

Why This Matters Beyond Just Using AI Better

Okay, so after reading all of this, it really just sounds like I’m saying “be more specific with prompts.”

But really, this principle isn’t just about being more specific and less greedy. It’s that if you can hit that sweet spot about conveying your intention but letting the LLM (or me) do its thing, then you’ll always come away with much better results.

As much as I would love to just say “write this article for me” and then it somehow reads my mind and writes exactly like I do. We are still quite far from that.

In computational design, I see this pattern constantly. Teams get excited about a new tool (Grasshopper, Dynamo, now AI) and think it’s going to solve everything. They want the tool to handle the entire workflow, make all the decisions, automate everything. They hack around the existing infrastructure, they put workarounds on almost everything, but none of it ends up being truly useful.

In fact, with both AI and computational design, I’d say that communication is the biggest hurdle. You get poor results because the intention is not clear or there’s not enough context about things. When that happens, you keep tacking on things or brute forcing your way, hoping it will fix it.

You can’t just keep telling ChatGPT “do it better” over and over again and expect it to know what you need.

The best computational design (and maybe AI) implementations I’ve seen are the ones that have a specific intention and design. They don’t try to solve everything at once. They understand that everything is a trade-off for something else.

It’s actually why when teams come to me asking about automation, the first thing I do is help them define the boundaries. What exactly needs to be automated? What should remain manual? Where does human judgment matter most?

This lack of context and understanding is probably why LLMs are still not good at working on critical things like writing the first draft of an article or creating the architecture of a codebase. There are just too many options out there, and the LLMs don’t have enough context on which ones are the most relevant to your specific situation.

Rob actually mentions this too when expanding the codebase of Giraffe. His CTO doesn’t let Claude generate any code for the core architecture without a review. The design of Giraffe’s codebase is unique to their requirements, and an LLM just doesn’t have that context.

“That higher order architecture thinking like what is the most elegant way of storing this on the DB or the data structure or the ontology that’s going to make sense... the LLM is not that useful... The LLM didn’t come up with that idea. That’s sort of we’ve had to work that up through first principles.”

Final Thoughts

Rob’s talk at the CEGS meetup gave me the language to articulate something I’d been practicing but couldn’t quite explain. I know I don’t have the ultimate way of thinking and using LLM but this principle has really given me some good use out of it.

Limits and intentionality is more than how to work with LLMs. It’s also a mindset for working with any abstract and powerful tool. That includes computational design.

The irony is that by limiting what we ask AI (or me, I will never get tired of this) to do, we actually make it more useful. And by being intentional about our requests, we get more reliable results.

Even though we instinctively know this, like how art is always constrained to a canvas or even making music has rules, we still crave the idea of the all-powerful tool that will solve everything for us.

And in a world where these tools can technically do almost anything, specificity and constraints are ironically where we make the most progress.

Want to learn where to apply computational design?

Subscribe to CodedShapes and I’ll send you my free guide on how to actually do that