A Better Way to Get Teams to Adopt Computational Design

To my readers celebrating Lunar New Year, Happy Lunar New Year to you and your family !

This time of the year is always little hard for me because I am here in Australia instead of home with my family in Malaysia. Then again, I have got some family here in Australia too. So I at least get to celebrate a mini-version with them.

The email titled "Might need help with some road alignment work.” sat in my inbox for days. It came from Grant, a senior civil engineer in the same company as me.

It’s not that I didn’t like Grant, it’s just that about six months ago, I did a project with his team that didn't go so well. I was sure that if they heard “computational design”, they would run behind a wall and hide.

For them to reach out meant a lot to me and I didn't want to let them down again. Last time, I promised revolutionary change without even understanding the kind of problems they were facing. By not listening to them, I had steered the project in the wrong direction, wasted their time, effort, and money.

I knew this time had to be different. I needed to listen more and understand their problems. I can’t just waltz in and take charge like I knew everything again. So, instead the traditional project kick-off meeting, I invited Grant out to coffee.

We spent an hour just talking about his team and the project. Their problems, what they weren’t happy about, and what success looks like for them. No scripts or automation or anything even remotely related to computational design. My job is to really understand what problems they had and if computational design was the right fit at all. I want to solve their problems, not create more.

It turns out that Grant didn’t have a project specific problem, it was a team workflow problem. Instead of doing a complete overhaul like last time, I started with a small proof of concept workflow on a low risk, small project. It wasn't interesting work but it gave us the space and time to work out all the kinks.

This extra time and space also allowed the team to become more comfortable with computational design and made adopting the new workflow much easier.

That was 9 months ago. Since then, Grant's team became champions of computational design in the Civil sector of the company. And it’s because computational design helped them where they needed it the most. Not because someone with “fancy” skills came in and change everything without even understanding their needs.

The true value of computational design comes from a place of understanding. And I learned that the hard way many times over the last few years. Grant’s team of initial hate of computational design was just the one of many other teams I have tried working with.

So, if you’re trying to get a team or anyone to adopt computational design. Here are some lessons I have been through in the last few years that might help you out.

Control and Trust Are Key Factors

It sounds silly, but it took me a long time to understand that people have a hard time changing tools, even when better options exist.

It comes down to trust and control. With familiar tools, even if they're slow, they can trust them to deliver results in a reliable and predictable amount of time. This makes project delivery simpler and reliable. On high risk projects, you want as much of that as possible.

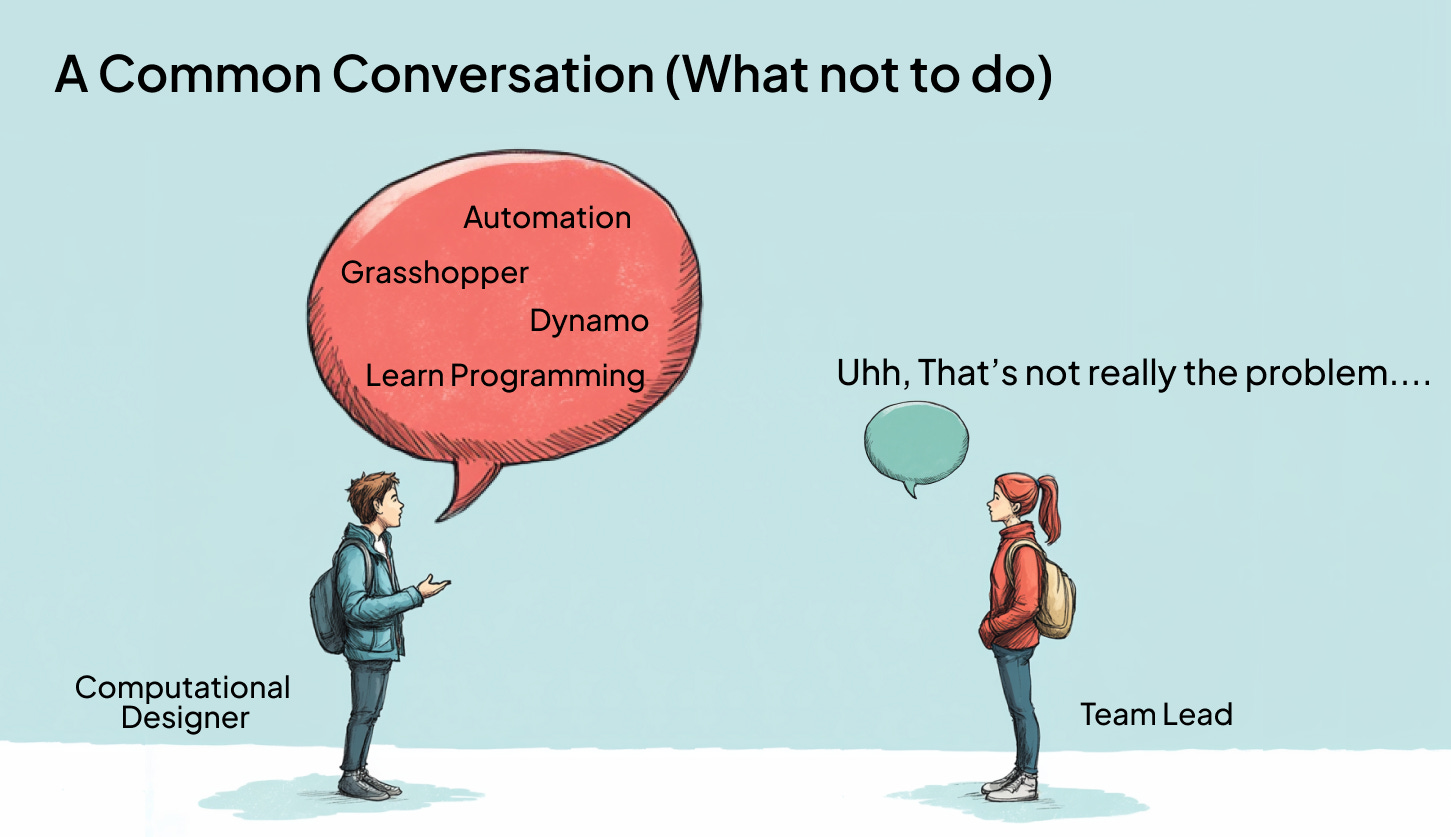

When a computational design person comes in to your team and starts shouting "Grasshopper will change everything" or "Grasshopper will 10X your productivity". You would close off to the noise because it’s too overwhelming. Also, no one has shown them how any of it actually relates to them.

Instead of talking about how great our tools are, we should work on showing how it can actually help them out.

This means instead of convincing them that Grasshopper or Dynamo is better, we should be showing them how the program can actually make their life better.

When we put in the effort to understand their problem, to speak their language, it opens up actual meaningful conversations about how computational design can and should be used. After all, we aren't experts in their field, they are, so we should be listening to them. Our role is to bridge the two worlds.

Start Small, Focused, and Low-Risk

If you’re new to the team, it helps to de-risk any first venture into computational design. This way, it at least guarantees some safety when experimenting. It also reduces the size of the request you make to the team.

Starting smaller means a lower risk which also means less pressure on everyone. That is always a good thing, especially if it’s your first time working with them.

It's easy and extremely enticing to only want to work on the big stuff. We (or at least I) tend to only want complex problems because we think that's where the interesting challenges are. But I have learnt over time that any problem is interesting as long as it delivers real value to people.

Define Clear Working Models

When I first started working with teams, I would let them decide our working relationship. I wanted things to grow naturally, I didn’t think it was worth defining anything.

Sometimes it was a developer and user relationship, where I build the tool and they just use it. Other times, it was a partnership, where we would work on the model together.

The problem with not being clear on roles is there was no clear accountability and no clear expectations on both sides. When things go wrong (which it always does on projects), it’s hard to understand what exactly caused the problem.

It’s not about pointing fingers, it’s to understand if there was a better way of working for both sides. It's already difficult understanding how computational design can help, you don't want to add the intricacies of inter-team politics on top of that.

So because of that, I have found it important to establish clear working roles. But I only do this after we’ve worked on the project for a little while. I still let the nature of the problem define our roles, but after I know how we are working, I would send an email or have a meeting to make that clear.

Now, before I start work, I normally ask them these questions that help me understand the type of working relationship:

Are you looking to up-skill someone in your team on computational design?

Do you just need this solved once, or are you looking for a tool to use over and over again?

If it's a tool, how would you train and distribute it to people?

Are you open to using new tools?

Do you have the time to train anyone involved to use new tools or processes?

Final Thoughts

Sometimes people come to us with their problems and sometimes we have to go to them. But every chance we get to work with someone is an opportunity to make a difference and solve something interesting.

I am very clear about what computational design can and cannot do but I am always optimistic about helping people. When we put people’s problems first instead of computational design, we always end up with better results.

Want to learn where to apply computational design?

Subscribe to CodedShapes and I’ll send you my free guide on how to actually do that