Why You Should Always Build Scripts With Others in Mind

What Happens When No One Can Read Your Script

It was a huge project that our team was working on. A project where we worked with the structural, civil, and construction teams to prepare a model and design package for the client. Out of our team of ten, three of us were focused on modelling: Arthur, Dianne, and myself. We were engaged to help bring a complex roof from concept design all the way to construction. That meant modelling every beam, every connection, and even the bolt placements in detail.

The roof was divided into three parts: left, right, and centre pieces. Each had different designs and could be modelled separately, so Arthur took the left, Dianne took the centre, and I took the right. Once we were done, we had to combine them and send one unified model to the client.

Things progressed as normally as a project could. It was chaotic, a few late nights here and there, but we were making good progress. We regularly updated the client on our progress, even sending rough drafts of the model for review. Despite the challenges, we actually met our deadline and submitted the model to the client on time.

About six months since we've started this project, most of us took some well-deserved time off. Not everyone, of course – the project was still ongoing and we needed someone in the office in case the client called. Still, we were pretty confident in our work, so we weren't expecting anything.

But one faithful day, Zack, the team's leader, got that exact call from the client requesting changes to the left side of the roof – Arthur's responsibility. It was a small change, but Arthur was off that day, taking his time off. Luckily, he told us where to find his scripts in case this happened.

So, Dianne and I opened that folder and went looking for the scripts. We spent a good 30 minutes clicking through folders and wading through files. All we could find was a Grasshopper script named "Roof Test" that was 120MB, which is enormous for a Grasshopper script. Surely that couldn't be it. One script? I myself had six scripts managing the right side of the roof and that was smaller than Arthur's side.

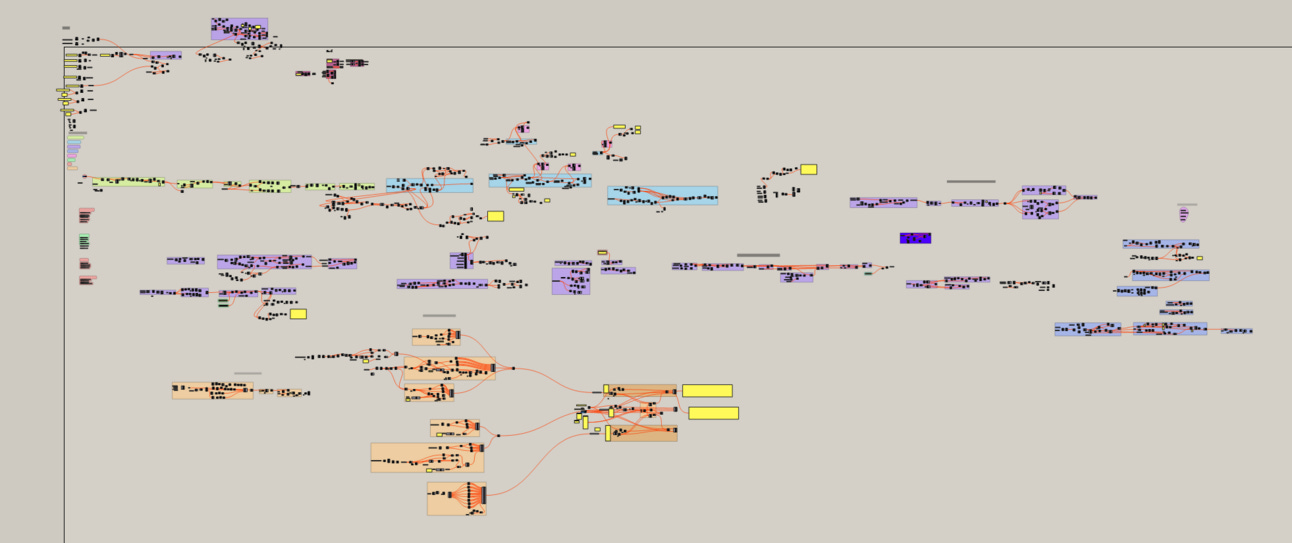

True enough, when I opened "Roof Test," I was met with this monster of a script.

I knew Arthur always followed scripting best practices, but this script was still huge. Even though it was well organized, it was still going to take some time to understand what was happening. Certainly more time than we were given by the client – and in their defence, they were only asking for a small change.

Over the next two days, Dianne and I poured ourselves over Arthur's script, trying to make sense of the script. We took it apart, dissected it and put it back together again. But we still couldn't understand it in time. We missed the deadline.

When Arthur came back, it still took him another full day to remember what he had done to the script and implement that change. It turned out that we didn't have the latest script, he had it sitting on his computer and not on our shared drive. We couldn't have implemented that change even if we had weeks instead of two days.

The Lesson - Single Points Failure

Even though it's my job to recommend people to replace their manual workflows with scripts, most scripts are single point of failures. Which increases the risk to a company. When you only have one person that knows how to edit and update the script, the risk of failure is pretty high. The manual way, although slow and painful, at least meant that more people knew how the process worked. It was less complicated and some times more robust.

Unlike other tasks – writing reports, manual modelling, or even software development – computational scripting in Grasshopper or Dynamo is mostly a solo activity. There are best practices and principles to help standardize the scripts. But for the most part, there is no way to enforce a certain way of scripting, which also means there is no common ground when working in a team.

With report writing, most companies will have templates and a style that you can follow for consistency. Even if you disagree with the template, there is at least some shared understanding of how the reports are meant to be written. We don't have that in computational design. Not yet anyways. Even in a similar field like software development, the emphasis on good code is less about performance and more about readability and how maintainable is the code.

When Arthur, Dianne, and I modelled each part of the roof, we became single points of failure. No one else but ourselves could understand our own work, which is a huge problem for a company. This is an even bigger problem if a critical process was automated with a script that only 1-2 people knew how to update and maintain.

Most companies are focused on the speed and ability to solve problems that we don't worry about how to maintain them moving forward. It's all well and good to use scripts to speed up workflows but we have to think deeper on how to maintain these scripts in the future.

The Documentation Challenge with Computational Design

Even with Arthur following best practices and organizing his script well, we still struggled to understand it. Good organization alone isn't enough, computational scripts often embody complex design logic that's hard to grasp without context. Because scripts are so tied with the way a person thinks and the context of the project, it's hard to understand someone's work if you aren't familiar with their previous work or the project.

However, we can reduce these risks through strategic documentation:

Design Intent Documents: Before writing any script, document the high-level strategy and key decisions. This isn't about how the script works, but why certain approaches were chosen. For example:

What are the main geometric principles being used?

What are the key parameters that drive the design?

What are the expected limitations or edge cases?

Critical Path Mapping: Identify and document the most crucial parts of your script that others might need to modify. In our case, if Arthur had documented which parts of his script controlled the roof geometry that commonly needed adjusting, we might have been able to make the client's requested changes in time even if we didn't have the latest script.

Change Logs: Keep a simple record of major script updates.

This isn't about tracking every small change, but rather documenting significant shifts in approach or new features added. Something as simple as: "Nov 15 - Added support for irregular beam spacing" "Nov 20 - Modified connection logic for edge cases".

I do this by saving multiple files of the same script as a rudimentary way of tracking the changes.

The goal isn't to document everything – that would be impractical. Instead, focus on documenting the critical information that would help someone else understand your process. My instinct and advice when it comes to documentation is to document the context and the reasons behind your script choices and trust that the person reading your script can figure out the technical specifics on their own. It's easier to figure out how a certain thing works rather than why it's put there in the first place.

What We Should Have Done

The easiest way to get over this hurdle is to have Arthur hold workshops or meetings that explain his script, but this takes a lot of time. It also meant that as the script changes, we have to keep having these meetings again.

What we should have done is have "design meetings" before we started work. It's where we discuss strategy and get a high-level understanding of how a person is going to tackle the problem. People in software development do this all the time. The meeting doesn't have to be long, it can and should be a quick 15-30 minute meeting that just goes through a person's thoughts on how he/she is planning to solve the problem.

Design Meetings

We should be having these meetings before we ever put a line of code or a component in a script. This achieves three crucial things:

It's a discussion, so you may uncover different types of solutions. You may even learn something from someone else in the room.

People around you know your plan. If they ever have to dive into your work, they at least have a sense of how your script(s) work.

You start to build an instinct for how someone likes to work. This discussion will help you understand the inclinations and behaviours of people, which will in turn help you understand their though patterns better.

Final Thoughts

It's very easy for all of us to get siloed. To work away on our own scripts without ever thinking about how someone else would understand our work. In software development, you're always working on a shared codebase, and there are systems like code reviews to give you feedback on your work. To make sure you're writing code that is aligned with the team's culture and practice. But you don't get that with computational tools.

We know that computational design can do great things, so when we work in a team, the emphasis should be on the readability and how maintainable the script is instead of how quickly we can make solve the problem.

Thanks for reading.

Subscribe to CodedShapes and I’ll send you my free guide on applying computational design.