Why Most Computational Design Solutions Don’t Scale

It's not intuitive after all.

Ahmed’s team is struggling to deliver drawings to a client on time

The culprit is a coordination task that takes up a lot of time. When they got a model update from the client, they have to ensure that there are no clashes between the structural and the services engineering model.

This means, someone or multiple people from both teams have to comb through all 36 floors of the model to ensure that nothing clashes and that everything still works. For each level, they have to makes sure:

The floor boundaries are aligned

Any new/moved penetrations are structurally and serviceably safe (like no holes in the floor where the columns are)

Any new/moved walls and columns are structurally safe

This always takes days to do because it’s hard to spot changes in a model unless you’re really looking.

It’s like playing Where’s Wally? 36 times every fortnight while your manager yells at you because you’re about to miss the deadline.

Needless to say, it’s stressful. Slow. And it always leads to late nights.

The Tool

That’s when Ahmed approached me.

He’d seen one of my presentations and asked if there was a way I could help. He figured there might be a way that we could at least make the process less painful.

So, I set off to build a solution for Ahmed and his team. Since time was of the essence, I did it in Grasshopper with the aim to make the script as user-friendly as possible.

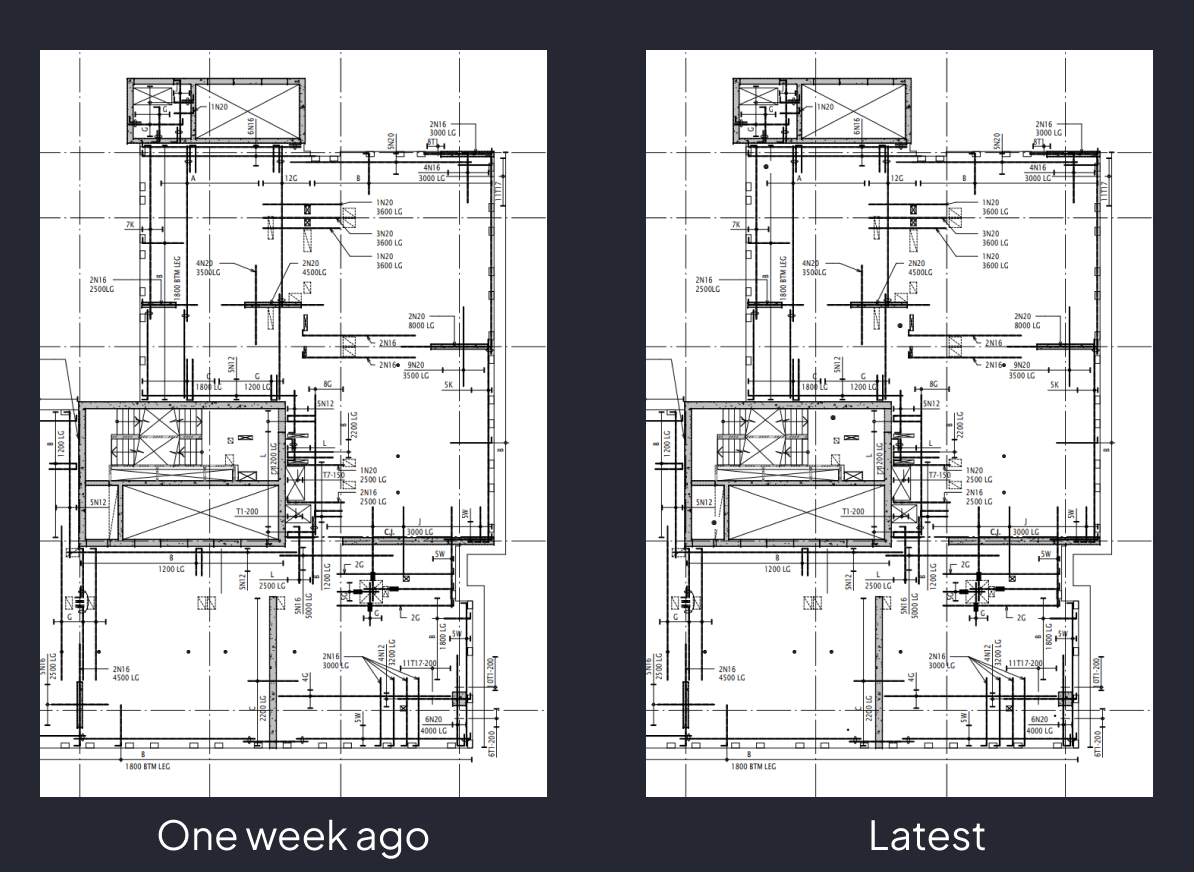

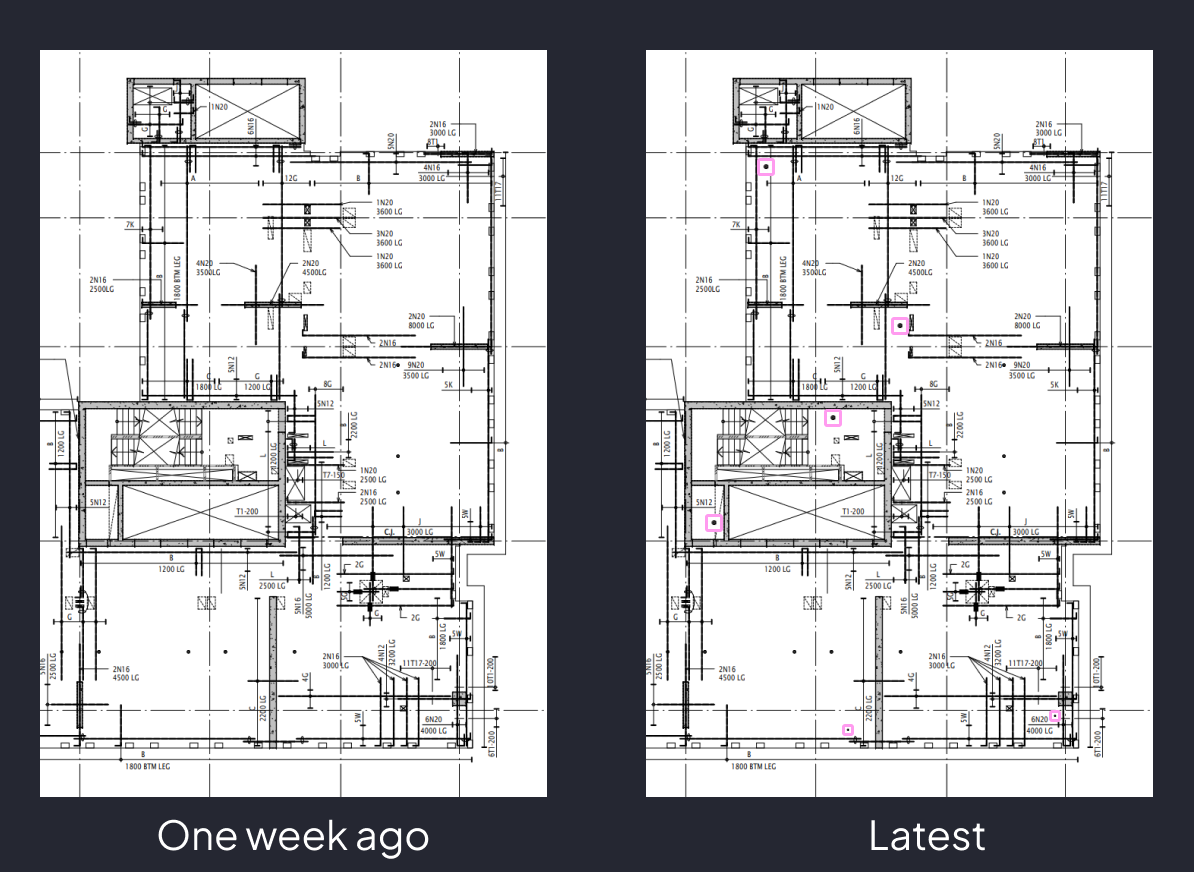

The script can’t actually solve the coordination for them but it can highlight the differences between the two model. Instead of engineers scanning the model floor by floor, the script highlighted where they needed to look.

Once the script was ready, I held a small workshop with all the engineers showing them the basics of Rhino and how to use the script in Grasshopper. There was some back and forth as I fixed up the problems in the script. Mostly edge cases that I didn’t account for at the start.

And, it went well.

Within two weeks, the team was running the script themselves. And a task that used to take four days, now just took one.

The Push to Scale

Ahmed was so happy with the solution that when the project finished, he came back to me with some ideas on how to make the solution robust enough for the entire company. He told me that the script just needed a few tweaks because this project had some unique elements that aren’t in other projects.

It made sense. He’d been through enough projects to see the pain first-hand. So we spent the next three months refining the script.

Even though it was only meant to be a month, we came up with more ideas and more features to help deliver the maximum value possible.

I added the ability to manage clashes, options to keep or reject the changes, and even the ability to generate drawings that highlighted the differences.

Campaigning

With the solution tested and ready to do, Ahmed decided to get in touch with the marketing team of the company to help with distributing the solution. They suggested we do a marketing campaign.

We started out with an email blast to the company, announcing the new solution. Then we held workshops using past projects as examples to teach people how to use the script. We even presented the tool and all it’s benefits in the company’s quarterly update.

And the result was.

0 new users.

It turned out that Ahmed’s experience wasn’t universal.

Yes, coordination happens on every project. But in 80% of projects, the changes were small enough that manual checking worked fine. Only the big and complex jobs really needed the script which was rare.

Everyone loved the solution. Some even tried it using the examples for themselves. But no one saw a need for it.

The business case of computational design

Most computational design solutions are built for a specific project or problem.

If that exact problem shows up again, it’s a bonus because you can reuse it. But this rarely happens outside the same project. Unless, the solution was made to solve a general problem in the first place than it has a chance at scaling. But more often, parts of the solution or the lessons leaned are what carries forward into a new solution, not the entire thing.

Because of how technical and seemingly limitless computational design is, it’s easy to focus on solving all the problems and forget about the business case of it. And I don’t just mean profit, though that is a big part of it. I mean the case for whether the problem is worth solving in the first place. Why invest three months of work into a problem that only happens once a year unless it’s really worth it.

The common misconception about computational design is that every solution is reusable. In reality, only those aimed at general patterns, like auto-dimensioning walls in a model, stand a chance of scaling, even then, it’s not always a sure thing. Project-specific scripts almost never stand a chance. I should have known that when I was working with Ahmed.

Final Thoughts

I’ve learnt to be skeptical when someone tells me that solving a problem for a project means solving a problem on every project. Because no two projects are exactly the same.

If a script was built for a project, it usually stays there. If it was built for a pattern, it has a shot at scaling. But either way, it’s never “build once, use everywhere.” Scaling something always takes more intention, time, and effort than people think.

That doesn’t make project scripts a waste. They deliver real value, reduce stress, and often are the ideas for broader tools. But the key is knowing which is which and being honest about it up front.

Want to learn where to apply computational design?

Subscribe to CodedShapes and I’ll send you my free guide on how to actually do that