Why Measuring Computational Design Value is So Hard

Metrics alone don't tell the full story

How do you actually know if what you’re building helps others?

I am in bed, desperate to sleep because I only slept four hours the night before and my, oh so, beloved mind decides to keep up the punishment with this question.

It’s a very simple question with no straightforward answer.

The best kind.

I’ve been in computational design for about 7 years now. I’ve built solutions that saved people time and effort. I’ve built solutions that were pivotal to projects. Without them, we could have never delivered the quality or the scale that was asked of us.

Yet, I’ve also built solutions that were used once, maybe twice (if I was lucky) then never saw the light again. Heck, I’ve even built solutions that no one asked for and well never got used.

But I have gotten better at this.

The years of experience has given me the instinct to know if computational design (CoDe) helps or harms a project. But, I still haven’t found a good way to measure it. And I don’t think I’m alone in this.

So, my brain finally let me sleep and I spent the next few days writing this.

A 2-part article on how to measure value in computational design.

Part 1 (this article) explores why it’s so hard to measure the value of CoDe.

Part 2 (upcoming) shows that I current do to ensure the work that I do is valuable for everyone. I’ll show my systems and process for “measuring” value in projects.

Computational Design Tools vs Solutions

CoDe in projects are different to making “conventional” tools for people. When we think of a “tool” or a “program”, we picture solutions made once, then reused over and over again.

But solutions made in the context of projects can only solve specific problems and don’t often get re-used. Parts of it may, but these solutions are never re-used without any tweaking.

That’s why when I speak and write about CoDe. I make the distinct difference between CoDe as tools and CoDe as project solutions. It’s also why I use the word solutions instead of tools when referring to CoDe done in projects.

CoDe tools are arguably “easier” than solutions because you can extrapolate the lessons from the software world. You can learn about what makes an effective software product and then apply those principles to the CoDe tool you’re making. But CoDe solutions are different entirely.

Since, they are developed during a project, they are often rushed, the creators are stressed and they solve a very specific problem. My question is, how do we know they actually help?

Computational Design in Projects

But, to understand why measuring the value of CoDe is so hard, we have to first understand how it gets injected into projects.

Early Inception

CoDe is the most influential when it’s brought in early. This means I’m part of kick-off meetings or any strategy before any work is done.

It’s important because this is where I get the chance to setup workflows that become the foundation of how the project operates.

Like choosing Python scripts over Excel sheets because I know the project will need higher performance calculations. Or knowing that coordination between drafters and engineers is crucial for the project, so I can setup something like Rhino to communicate changes in the model instead of PDFs to prevent double handling of data.

When I am early to projects, I get to set these computational workflows that becomes the core process for the project delivery.

As great as this sounds, you risk being locked in to a computational process that is misaligned with what the project actually needs. Using Python sounds great, but not many engineers know Python. So who will maintain it ? What happens if there’s an error in the code ? Also, if the process is too rigid and doesn’t adapt to project conditions, it might actually slow the project delivery instead of speeding it up.

Exploration

As the project starts and people have a handle on what delivery looks like, there’s usually some exploration to do. Like what methodology to follow, what and where the pain points are, and how the clients are behaving in project conditions.

When we think about CoDe in this scenario, it shift from using CoDe to define systems, to using it as a way of exploration. It means I get to test out some CoDe workflows on the project without the risk of committing to them.

It’s rare but I find that this situation happens when the timelines and budgets of projects are not as tight and people are more open with trying new things. In fact, if there’s a repeating pattern within the project, there’s a chance to create a tool instead of a solution.

In Progress

Then, we have the most common way of CoDe entering projects (at least for me)

It’s when people are looking to replace or enhance their current processes on a project that is well under way. They know what project deliver looks like. They have done things manually and long enough to understand the problem well.

They could be spending too much time on data entry or need to speed up their current manual workflow. Knowing their problems well, makes it easier to develop a CoDe solution.

But most people don’t reach out for CoDe because they don’t know they even have a problem. Things are slow, yes, but they are working and unless they cannot make their deadline, they might not reach out. Which brings me to my next point.

Fire fighting

This is when the project isn’t progressing well or the team has taken on too much. Either way, people are desperately looking for ways to alleviate the crisis.

It’s situations like this that I find make people turn to CoDe because they think the promise of automation will save them. And, sometimes they are not wrong.

Any solution created in a rushed, stressed and tired environment will always just be a band aid to the current problem. Maybe that’s what the project needs but any hope of long term use goes out the window.

Measuring Computational Design

So, with all of this, you’re getting some inkling about the value of incorporating computational design but how do we actually measure it’s value ?

We all understand that automation and digital processes have some inherent benefit. But how does that help you when you’re choosing to either recruit more engineers or contract a computational designer ?

Well, the first instinct that comes to mind with any kind of “automation” is time saved. As in, if it takes me 30 minutes to do something manually but it takes me one hour to make the computational solution for it to be reused repeatedly on the project. Then, you can start tracking that time saved.

But only focusing on time saved doesn’t tell the full story. It’s incomplete at best and misleading at worst. In fact, focusing on any one metric alone is bound to be misleading.

Let’s look at some of the common metrics I have seen used when trying to measure the impact of computational design in projects.

The metric of time saved

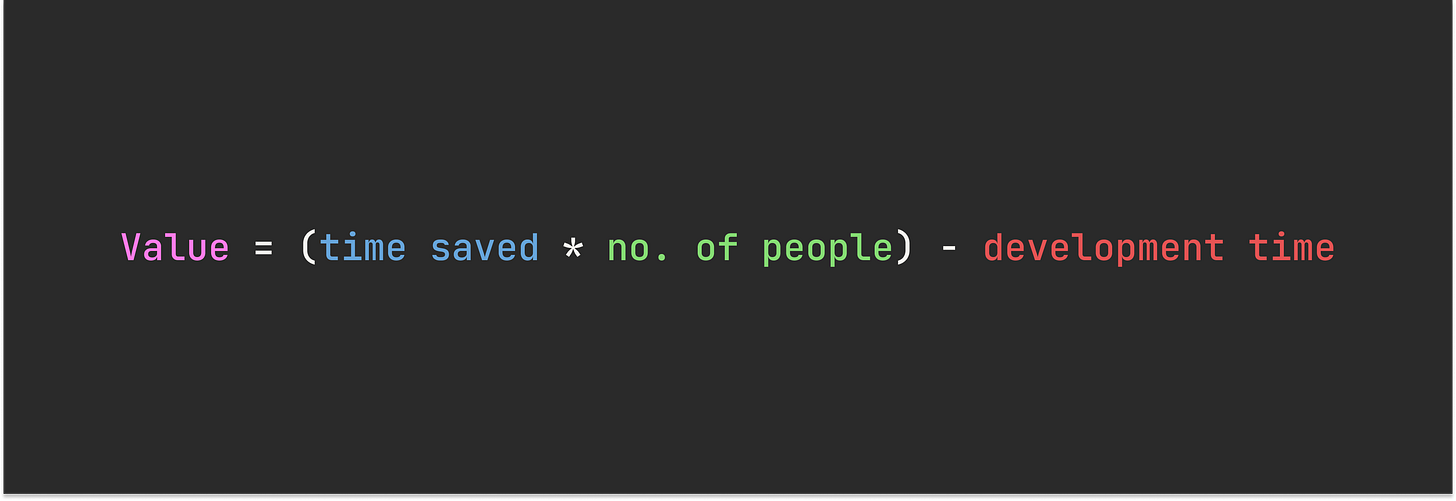

This is most common metric is time saved. It’s a simple equation.

First, we calculate how much time is saved with the CoDe solution as, compared to the manual way. Because even with a CoDe solution, you still have to spend some time using the workflow even if it is quicker.

Then, we can figure out the actual time saved by factoring in the number of people likely to use the tool and the development time.

And the reason why this is the most common metric used is because you can put exact dollar figures to it. By assuming an average hourly rate for the users and an hourly rate for the CoDe designer, you can price the value. And if you’ve ever talked to managers in companies, they love dollar figures.

But only using time saved as an indicator of value breaks down quickly. Because if you’re looking to maximize the value, you will either rush the development (keeping development time low) or hire less experience CoDe designers (keeping developer rate low). Both are pathways to a lower quality and less robust solution. The lowered robustness means, you have to spend more time fixing the solution later on, which drives the value down again.

Even if you do the right thing like hiring correctly or allocating a proper amount of time. When you only track time saved, your solutions don’t get the right bandwidth for proper development and maintenance because there’s always a strong time pressure to deliver things quicker.

The metric of reducing risk

Another reason to use CoDe in projects is to reduce the overall risk. By automating tedious operations, you’re more likely to reduce human error. Eliminating as much manual data entry as possible is a good example of this. Because as a fellow human myself, it’s very easy to type “32” as “23” and that can mean the world of difference.

The other side of the coin here is that we’ve just shifted the human error onto the CoDe solution itself. If there’s an error in the code, the effects are far more devastating because of its scale of impact. One person typing something in wrong is better than a solution that 10 people uses giving out the wrong answer.

But like with any automation, you always have that risk. Like instead of storing things on paper, you put them in a hard drive that can get corrupted. If you have systems and processes in place to help (like testing or stage reviews) than the risk of the CoDe solution having an error is less likely.

Whether human or not, how do you quantify the value of a risk avoided? How do you put a dollar figure on a disaster that didn’t happen ? When you time about the metric of time saved, I can easily run simple calculations to figure out if the CoDe solution is worth the investment. It’s trickier with risk.

The metric of increasing quality

The last major reason to use CoDe in projects is to help increase the quality of project delivery.

If I can re-produce an expert’s process into a script and hand that script off to all the graduates, I effectively have just made an army of experts on the project. I can essentially turn a qualified, high value manual process into a repeatable system that can be used by anyone.

But “quality” is subjective and it’s value is also hard to quantify. When we go shopping and we compare the cheap wood table to the handcrafted wooden table. We know the price difference is due to the craftsmanship but we cannot quantify the value of it. We cannot answer the question why exactly does the handcrafted table cost X more than the wooden one.

We can’t measure the amount of man hours it takes per table nor can we use the difference in material as a way to justify it’s cost. We just instinctively know one is better than the other but we cannot put a quantity to how much it’s actually better.

Well, that is the same with certain CoDe solutions. Where the projects are enhanced by it. It may cost more but clients are arguably getting a better service and project delivery as a result.

Other fields have the same problem

Okay, but rejoice.

I think.

Because we aren’t the only ones struggling to understand the value of our work. Software developers have been arguing about productivity metrics for decades. They’ve tried to use lines of code, story points, pull request numbers, etc. But alone, none of these metrics come close to the true value of their efforts.

Even in our industry, the Architect, Engineering and Construction (AEC) industry, we struggle to get a metric that represents the value of effort. Was the construction a success because of an engineer’s methodology ? Because of the architect’s early design? or because there was an extremely skilled builder ?

The argument is that, everyone working together is more valuable than the sum of it’s parts. But how do we measure the impact of individuals ? Measuring the impact of knowledge work is genuinely difficult, and every field that’s tried has run into the same walls we have.

The only difference is that other industries had the time to understand how to divide the roles into more meaningful categories and tiers while CoDe is still too new.

When I say “Senior Structural Engineer in residential buildings”, you probably have a good idea in your head about what this person does. But “Senior Computational Designer” doesn’t say much. The “senior” signifies some competence but still doesn’t guarantee value.

We cannot choose only one metric

One thing is clear though, you cannot choose a single metric because alone, any single metric incentivizes a bad situation.

Chase only time savings and everything you make is rushed and will break easily

Chase only risk reduction and everything will be over designed

Chase only quality and you risk perfectionism and never deploy

You have to look at all the metrics for any given project to understand the full story. Even if you cannot put exact figures to it. A single metric alone doesn’t tell the story but together, they give you a better understanding of the value of the solution itself.

I don’t know the right answer to actually measuring the impact of CoDe but one thing is clear that value cannot be defined by metrics alone.

In the part 2, I’ll share the system, process and mindset that I actually use to help me figure this out.

If you found this useful, subscribe to CodedShapes.

I’ll send you my free guide on applying computational design at work as a thank you