What, This is Computational Design ?

What did you think it was ?

I was on a call with Nat, a civil designer, as she walked me through the painfully manual process of adding asset data to elements in Civil 3D. There was something weird about the model, she had merged a few 3D solids that originally came in as smaller blocks.

“Why did you merge these solids?” I asked.

“We merged them so we’d have fewer elements to add asset data to,” she said. “If your script can automatically merge them too, that would be great.”

“Okay,” I replied, “but wouldn’t it be better if the script just added the data to all the elements, so you don’t need to merge them at all?”

She paused. “But that would mean there are more elements to add data to.”

“Yes,” I said, “but the number of elements doesn’t matter anymore—because the script handles it.”

She nodded. That was the end of the conversation. Two weeks later, she no longer merges or manually adds data. It’s all automated.

After we submitted the final model to the client, she turned to me and asked, “This is computational design?”

I nodded. “What did you think it was?”

She laughed. “I thought computational design was only for those fancy-looking towers—not for asset data in Civil.”

Trying to sound wise, I said: “Computational design is whatever you need it to be. It’s just about using computers to solve problems.”

It's a story as old as time.

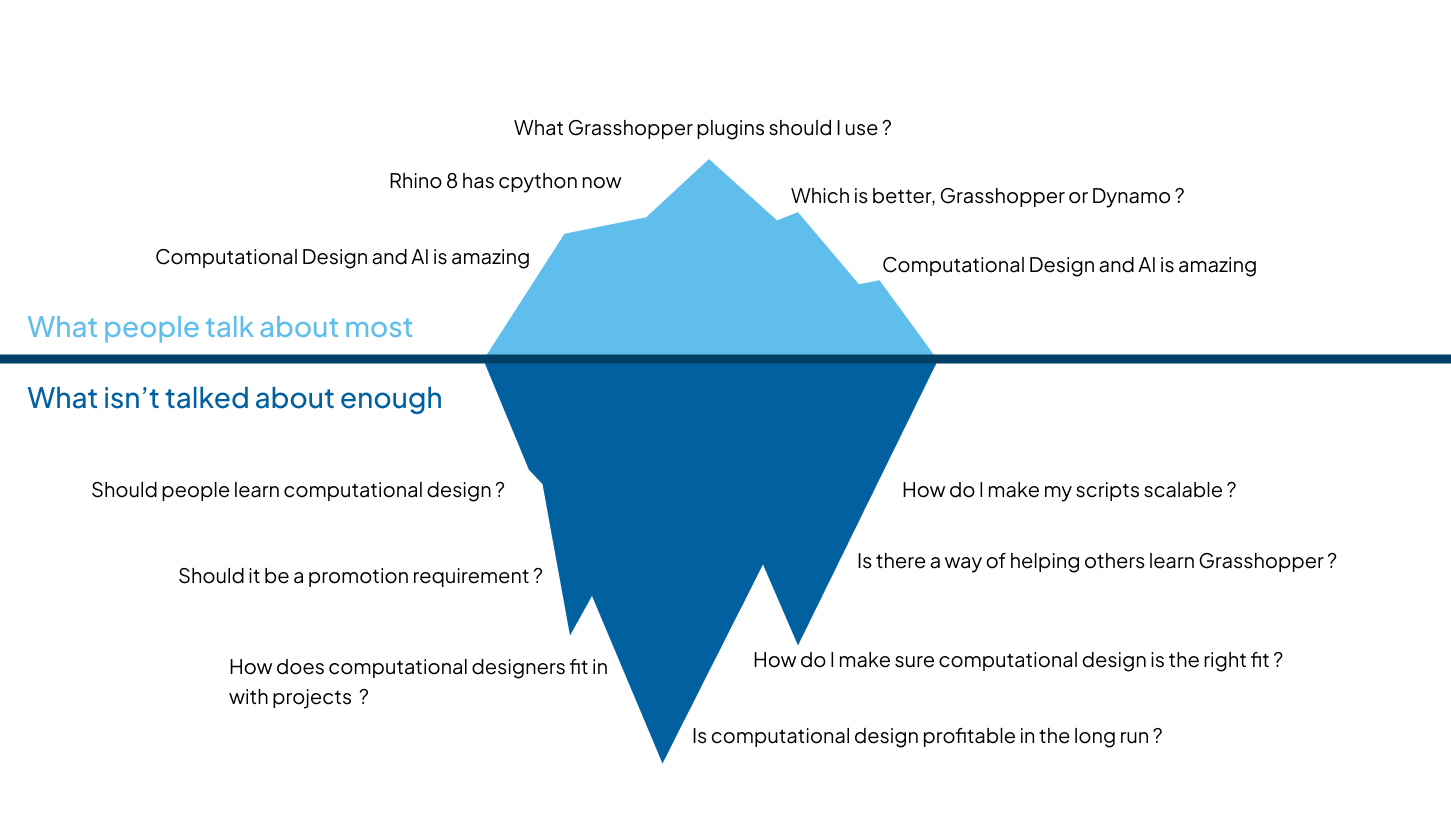

The biggest irony of computational design is that we often only show off the fancy, flashy stuff. We think that’s what will attract people but it often ends up pushing people away.

The reality is that behind every complex model is something far simpler: numbers and letters. Okay, it's more complicated than that, but when you break it down, it really is just math and text. The skill then is knowing how to weave them together to solve real problems.

And yet, it's still easy to feel overwhelmed.

Scroll through social media and you’ll see people doing wild things, messing with AI, hooking up chatbots to 3D models, running optimization algorithms that feel like magic. It’s easy to zone out. Easy to assume it’s just a trend. Easy to feel like it doesn’t apply to you.

But computational design isn’t a trend. And it’s not just for mega-projects with unlimited budgets. It’s a normal, practical field. One that’s been around for a long time, we just didn’t have a name for it. What makes it different is that it’s visual, and that makes it easy to show off online. Every small win can look like a groundbreaking innovation.

I’m not saying the flashy stuff isn’t important. Messing with AI and making complex models is exciting and valuable. It’s just not everything we do. And it’s not all we can do.

At its heart, computational design is about solving problems, of all shapes and sizes, with computers.

And that's the funny thing. We need more problems to solve but we keep unintentionally pushing people away by only showing complex things. Domain experts—engineers, architects, drafters—don’t reach out because they’re convinced that computational design isn’t for them.

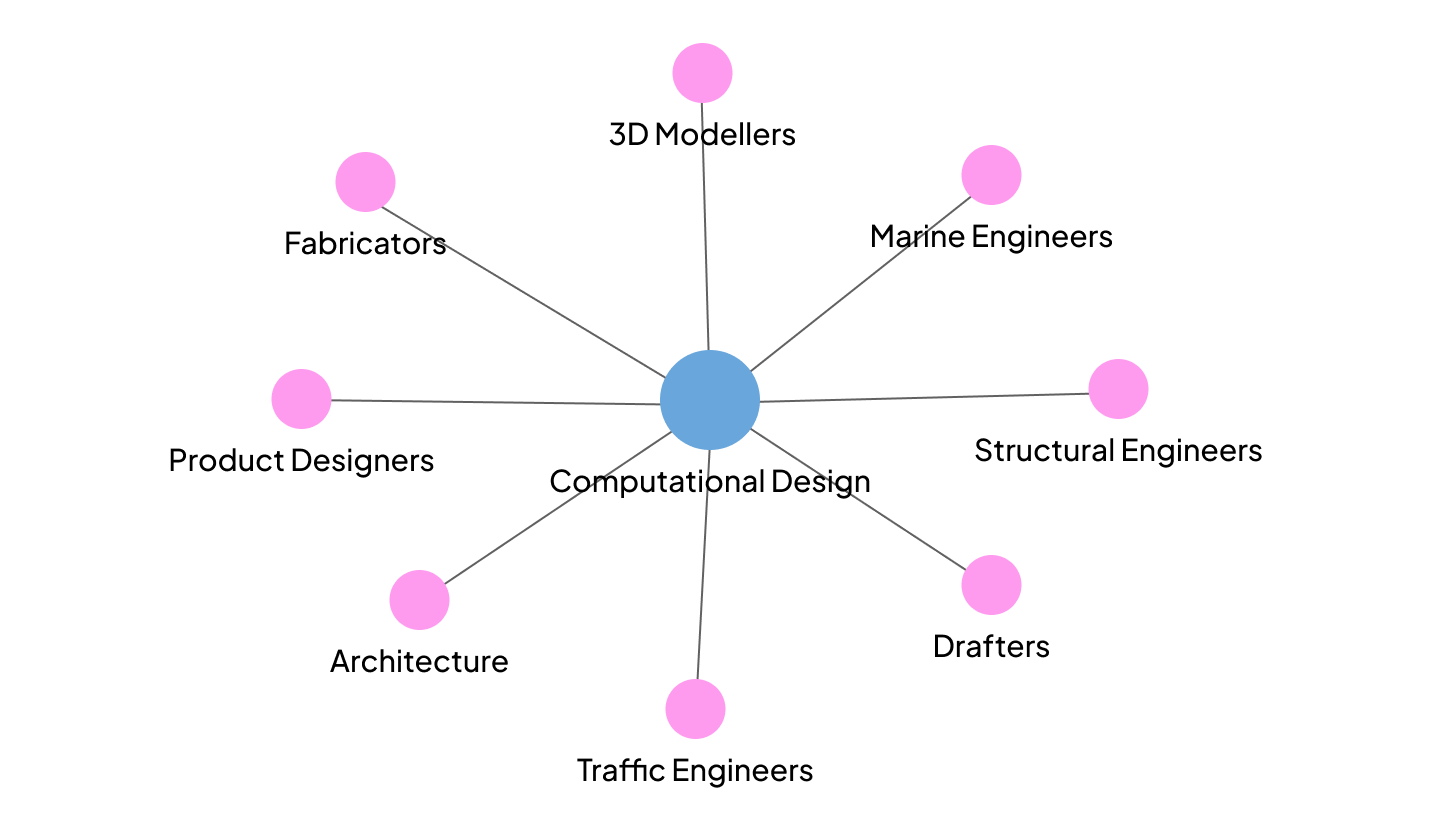

And we need them. There’s no computational design without engineers, architects, drafters, product designers, marine engineers, you name it. We rely on others to define the problems. Our expertise is in using computers to explore solutions. But to do that well, we need those problems in the first place.

It's a huge problem. I know computational design is valuable. I’ve seen how powerful it can be. But often, people don’t know when it’s worth applying. Or they don’t think it applies to their work at all.

We have domain experts stuck doing manual work, and computational designers with amazing skills but not enough problems to solve.

Somehow, we’ve made computational design look too unapproachable—when in fact, it’s most useful when applied to the small, painful, repetitive things no one wants to deal with.

That’s why I started this Substack, to bridge that gap. To show that computational design isn’t just for the “design elite.” It’s for everyone who works with rules, geometry, or repetition.

It's why, you might already be in a great position to learn computational design. Most people put their head down and just focus on their own domain, if you can look up every once in awhile to dabble in another field, you will broaden your horizon. Computational design might just be that other field.

Even having just a basic understanding of computational tools, or knowing how they work from a high level, is incredibly useful. It helps bridge the gap between your field and computational design. It makes collaboration easier. And it gives you more control.

Even basic computational skills, just knowing the tools or how they work from a high level is already immensely useful. It helps to bridge the gap between computational design and your field. It's also why I try to learn as much about the field I am working with as I can.

That’s also why I try to learn as much as I can about the field I’m working with. I like to joke that I technically know just enough to be a graduate engineer, architect, drafter, or construction coordinator—but I’m a master in computational design. And honestly, I think you should do the reverse: know enough about computational design to leverage it for your domain.

So if you’ve ever thought, “This isn’t for me,” maybe it’s time to revisit that.

Want to learn where to apply computational design?

Subscribe to CodedShapes and I’ll send you my free guide on how to actually do that