What Happens When No One Understand What You Actually Do?

Communication and understanding are the pillars of any good design

I should have asked more questions at the beginning.

But I didn’t. And now, at 2pm on a sunny Tuesday, I’m paying for it with a Teams call from Marcus, a director at the company.

His voice booms through my headphones, loud enough for the entire office to hear.

“We aren’t moving as fast as we should be. Where we are is where I expected us to be four weeks ago. I need you to own the central structure and we need to move faster”

I look down at my desk. Was my keyboard always that dirty? Maybe I should get a cloth to clean it. I wonder why, I mean I don’t eat at my desk, maybe it’s just the dust...

I snapped my attention back to Marcus, when he said my name again.

“We need someone to take full responsibility on this. We are far too busy and you need to get this structure working. You know computational design and the geometry, you now need to understand how this is going to work”

When he stops to breathe, I finally get a word in. “Marcus, we need to talk about expectations here, I can’t possibly own...”

“No. What I am asking for is some initiative, not some incomplete model. You need to stop relying on others and use your own instinct. I need you to own this. Go ask for support from whoever you need. Just get the job done.”

Then, he hangs up. I’m left staring at my keyboard, wondering how it got so dirty.

This call doesn’t surprise me. And the truth is, I set myself up for this failure from day one.

When the project first started, I was brought in for “computational design support”, whatever that meant. The scope was vague and my role was unclear. Heck, I didn’t even know what I was delivering. But instead of asking the uncomfortable questions upfront, I nodded along, eager to prove I could help. After all, Marcus was a director and my manager told me to just keep him happy.

But I knew this wasn’t going to go well.

What exactly do you need from me? Where does my responsibility end and the structural engineers’ begin? What decisions am I qualified to make on this project?

I never asked these questions and Marcus never offered. We just said “we’ll figure it out”

It was uncomfortable but at least manageable in the beginning. Write a script to model some geometry, support the team. But “support the team” is dangerously broad when no one defines what it means.

Week by week, my scope expanded. First it was just geometry. Then, I needed to do the structural analysis. Then, I needed to design the members. Suddenly, I am being asked to make structural decisions. Decisions that I’m not qualified to make.

Every time I pushed back, the response from Marcus was the same: “You’re the one with the model. You figure it out.”

This is what happens when you skip the alignment work at the start. You don’t just waste time and effort, you start spiraling down into a lose-lose situation. I am spending more effort doing useless work and people get angrier because the work isn’t valuable. It’s negative cycle.

I was living proof of the coordination tax I’d written about before. Except this time, I was the one who’d chosen not to pay it upfront.

But as bad as things got, I still wanted to help.

So, I went around asking for support.

I spent two hours with Hannah, our resident expert in vibration for complex structures. I explained the project context, showed her the model, walked through the modeling requirements. She gave me some pointers, but she was too removed from the project to really help. She didn’t have the context because no one had taken the time to properly onboard anyone.

So, the next day. I went to Mike. He’s done a lot of complex structures before, he’ll know what to do. But no such luck.

The day after that, I talked to Lucas. He knows how these structures get built. He’ll have some ideas. Same thing....

Everyone I spoke to was willing to help, but they all lacked the project context to give meaningful input. And they were all too busy with their own projects to dive deep enough to get that context.

By day four, I’d run out of people to ask.

All I could do was stare at this behemoth of a model, realizing that no one actually understood what this project needed. Not Marcus. Not me. Not the team.

We’d all just assumed we were on the same page. That we knew what “supporting the team” meant. And now, weeks in, we were discovering we’d been reading completely different books all this time.

Was I just not good enough ?Should I just stop computational design. Take some time and learn “traditional” structural engineering ?Do I even want to do that ? That doesn’t sound like something I want.

I sit and stare awhile more.

My manager walks by and taps me on the shoulder, then gestures us to go into a meeting room.

“So, Marcus gave me a call,” he says.

“He told me about the project and how it hasn’t been going well. He thinks you’re not communicating enough and that you should fly to Adelaide three days a week. Marcus thinks it’s the distance that’s causing all these problems.”

Should I tell him that it’s not the distance? That it’s the lack of clarity from the start?

I decided against it. So I make some commentary about thinking it over, and we both leave the meeting room.

It’s funny. I was being told I wasn’t communicating properly, when the real problem was that we’d never properly communicated anything from the beginning.

More face time wasn’t going to fix unclear roles. Being in Adelaide wouldn’t suddenly clarify which decisions I was supposed to make. Flying there at 5am three days a week would just mean running in circles in a different city. And last I checked, circles are the same anywhere you go.

The problem wasn’t geography. It was alignment. And we’d skipped that step entirely.

I went home that night and thought about what I should have done differently.

The answer was obvious: I should have asked all the hard questions at the start.

What specific deliverables do you need from me?

What decisions am I qualified to make versus what needs engineer sign-off?

Who’s responsible for structural validation?

What does success look like for my role on this project?

When we say “own it,” what exactly does that mean?

But Marcus was a director and I was afraid to make him even more mad than he usually is. But that makes it even more important to ask those questions.

They might make you seem difficult or unsure. But you know what’s more uncomfortable? Being three weeks into a project, realizing everyone has completely different expectations, and having no way to course-correct without major pain. Well, that’s what I am dealing with on this project.

So, enough is enough.

The next morning, I scheduled a call with Marcus and pulled my manager in.

“Hi Marcus, I understand this project hasn’t been progressing well, but this is too far outside my skillset. I want this project to go well, and for that I need more support. I need engineers on the project to help me assess the things I don’t understand.”

Marcus pushes back immediately. “We don’t have the budget for more engineers. You need to figure this out.”

“I understand the constraints,” I say. “But we need clarity on roles. I can handle the computational design and geometry, but asking me to make structural decisions I’m not qualified for will only create bigger problems down the line. Let’s define exactly what I’m responsible for and where I need support.”

That call went on for an hour and a half. We discussed the project, my role, what support looked like. It was uncomfortable. Marcus was still... Marcus. But this time, I stood my ground.

And it worked. Well, not perfectly, Marcus is still unreasonably demanding and the project is still challenging, but I got a few engineers assigned to support the structural decisions. And more importantly, we now had clarity on who owns what.

The project is still ongoing as I write this. It’s still difficult. But now when problems arise, we don’t waste time arguing about whose responsibility it is.

Well, technically we established it three weeks late. But better late than never.

The Lesson

Understanding is the foundation of all good projects. Every hour you spend upfront clarifying scope, roles, and expectations will save you days of confusion and conflict later. This isn’t about being difficult or bureaucratic. It’s about respecting everyone’s time and expertise.

Even if I was speaking to a director of the company, I should have been more upfront about what exactly I was doing and what that meant.

Vague agreements are future conflicts. “We need computational design support” means nothing. “You’ll model the geometry and flag potential structural issues for engineer review” means everything. The more specific ysou can be about deliverables and decisions, the fewer problems you’ll face. Also, the clearer the actual problem becomes.

Enthusiasm isn’t a project plan. I pride myself as a problem solver, so I was so eager to help that I said yes before understanding what I was saying yes to. Even though there was pressure from the project and Marcus to just say yes, it’s not helpful at all. It’s like promising a false hope.

Yes, I’ll solve your problem. Then 3 weeks later, actually I can’t solve it. That’s a bad deal.

Real help comes from clearly understanding the problem first even if it means asking the hard questions from unreasonable people.

“Own it” is meaningless without boundaries. Taking ownership doesn’t mean accepting unlimited scope. It means taking responsibility for your defined part of the work. If someone tells you to “own it” without clarifying what “it” is, that’s a setup for failure. You were never going to do well in the first place.

The uncomfortable questions are the important ones. The questions that feel awkward to ask at the start about scope, authority, qualifications, are the exact questions that will save you later. Ask them early, even if it’s uncomfortable.

It’s weird for me because all these lessons makes the process more “corporate”. I would love to be able to just “hey, got a problem? I’ll solve it”. We shake hands and I come back with a perfect solution. But that’s not reality.

The truth is that to be effective, we need to understand context holistically first. We need to know where to move and what kind of work will get us to the goal. Not just say yes to everything and hope for the best. “We’ll figure it out later” is often a recipe of disaster.

The reality of computational design in projects

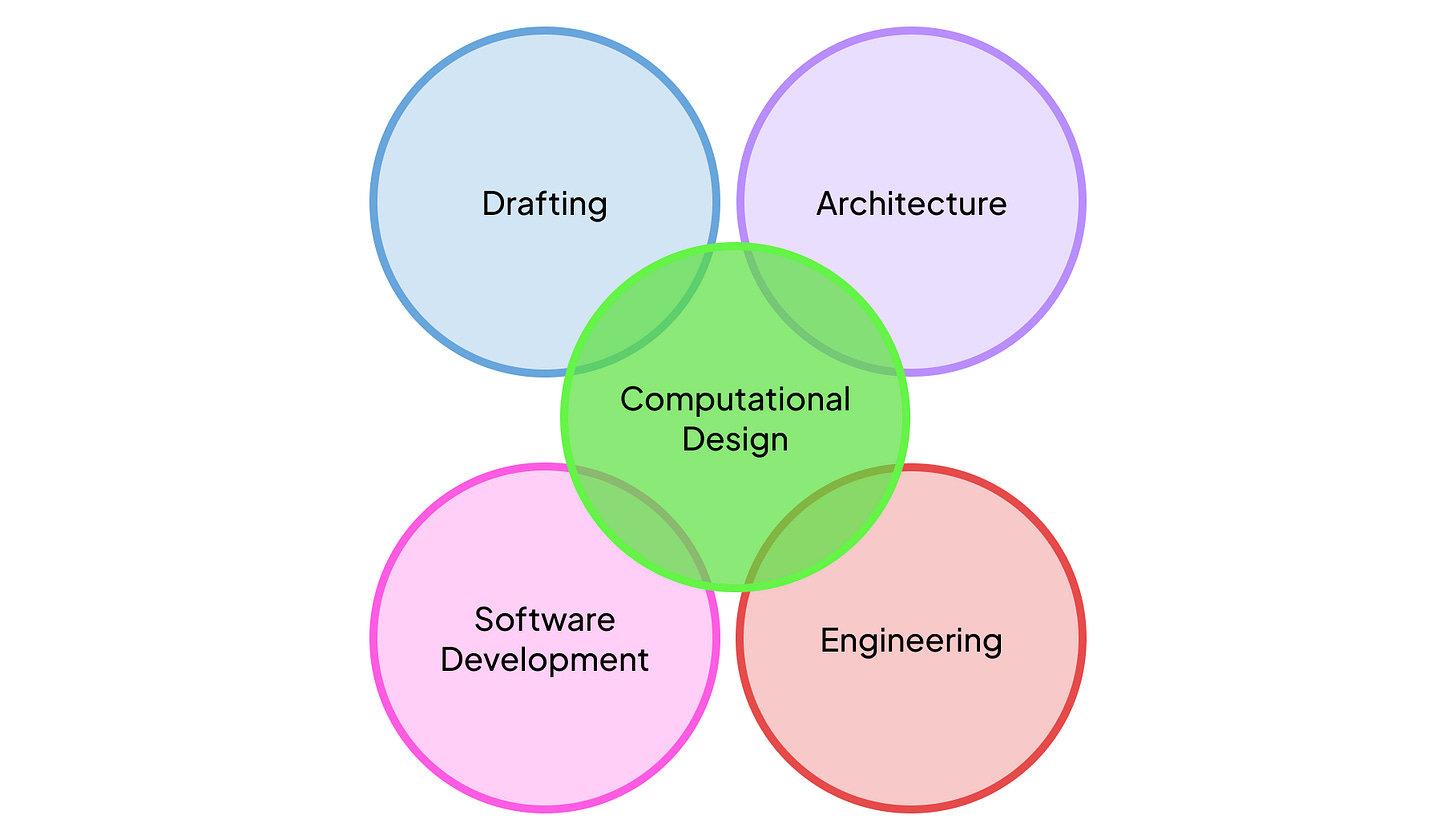

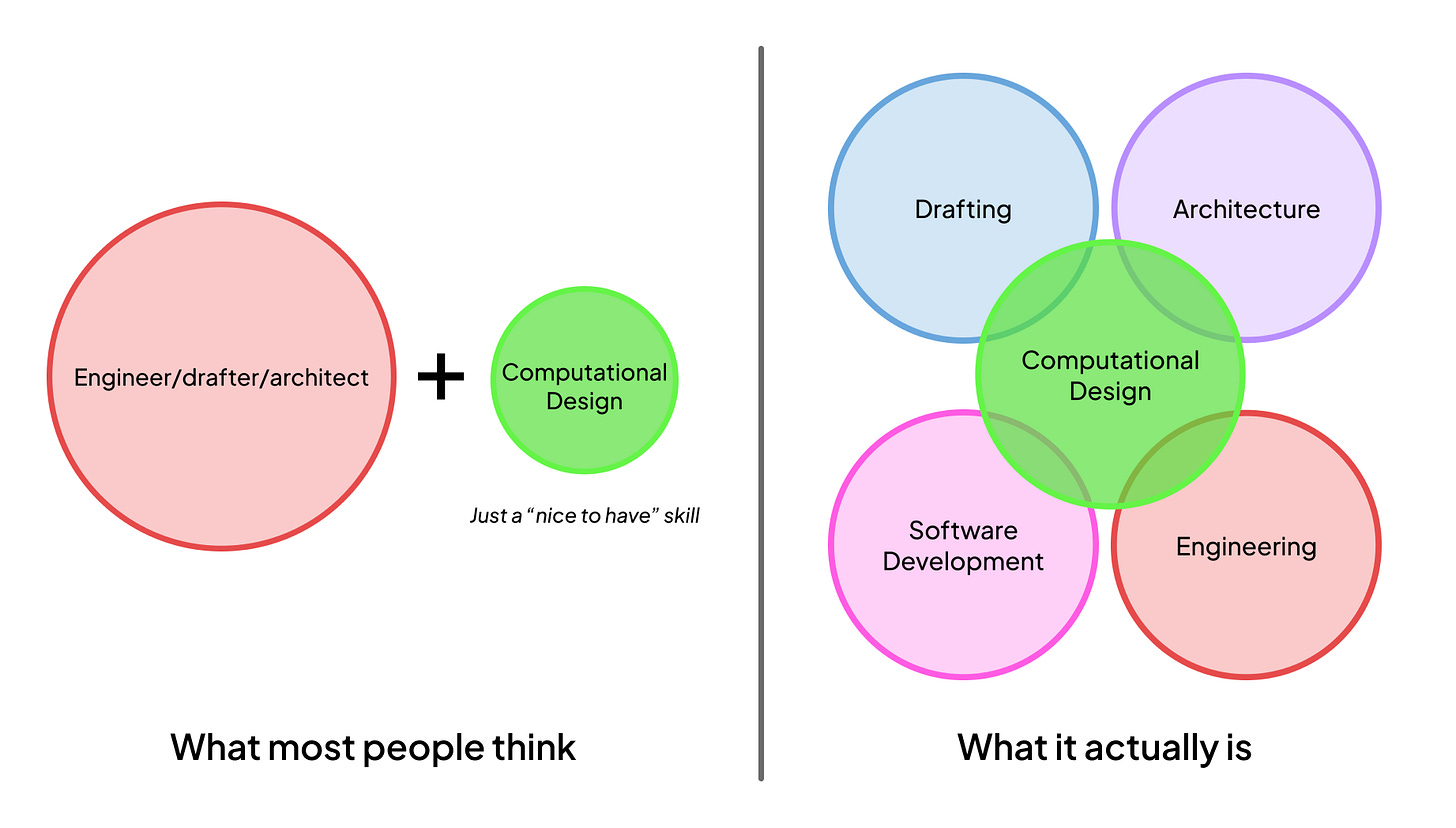

I think this keeps happening to computational designers because our role is still poorly understood. Especially because we sit at the intersection of multiple domains.

People see someone who can work with geometry and code, and they assume we can just “figure out” anything technical. But that intersection is its own specialty, it’s not the same as being a structural engineer, or an architect, or a software developer.

When I spend my time trying to become a structural engineer, I lose time becoming a better computational designer. These are different skillsets that require different focus and different expertise.

Without understanding about what computational design is and isn’t, projects default to treating us as “engineers with extra features” or “drafters who code.” That’s when we end up responsible for decisions we’re not qualified to make.

The only way to prevent this is through clear communication from the start. Not when we hit a wall. Not when someone’s frustrated with progress and about to quit. We have to do it from day one, as uncomfortable as that might be.

Final Thoughts

I wish I could say all my work now starts with perfect alignment. The reality is that I still sometimes chicken out of asking the hard questions upfront, especially when the person across from me is intimidating or impatient. But I’m getting better at it, particularly on projects I initiate myself.

Now, I frame uncertain work as discovery or exploration, especially when we really don’t know what we’re working with. I’m explicit about my skillset and boundaries. And most importantly, I don’t move forward until we have clear, shared understanding.

I’m learning to accept that clarity at the start is the kindest thing you can do for everyone involved. Even if it means people see you as “difficult” or “rigid” at the start.

The Marcus project is still ongoing. It’s still challenging, and I’m still constantly negotiating what my role is. But it taught me that the time you spend understanding the problem upfront is never wasted. The time you spend fixing misalignment later always is.

I’m still learning to navigate the balance between being helpful and being realistic about my limitations. I still don’t have all the answers. But I know now that starting without understanding isn’t just unhelpful. It’s actually harmful to progress.

And I know that no matter how much someone like Marcus demands immediate action, taking the time to understand first is the only way to actually move forward in the right direction.

Thanks for reading. If you’ve enjoyed that, consider subscribing.

When you do, you’ll get a free guide on how to apply computational design to your own work

Excellent analysis! This really hits home. It’s so frustrating when the goalposts keep moving and expectations are never properly defined. I wonder how you're supposed to truly 'own' something if the requirements are a shifting mistery? It's like being asked to write code without a clear spec.

For me, the biggest question is how to do the alignment up front; Especially when dealing with people that have no clue about what computational design is and how it works. In my experience, Talking about expectations with people that have no frame of reference for the work we do, usually doesn't result in valuable targets, often we discover that we need to throw out our entire approach a couple of times during the project.