This Is What Working With a Computational Designer Should Look Like

Okay, it's not the only way but I think it comes close.

Did I ever tell you about the time I cost a client a 50% delay and $8,342 because I was too eager to start building?

Well, it went something like this....

I was in a zoom meeting with a client, George. The conversation was going well. Every time I made a point, George would agree and even add on to it. Everything felt in-sync. We even ended up talking for two hours instead of the allocated single hour. It may have been our first time meeting but we talked like we’ve worked with each other for years.

I was feeling really good about it and George seemed as excited as I was.

When the call ended, I immediately started drafting up the proposal and sent it that same night.

I expected another call with some follow-up questions, maybe about the payment or the scope. But what I actually got was an email with George’s signature.

I then sent the first invoice and again, it was paid on the same day. Which is rare.

I then sent another email requesting files and models to get started. Again, I got it within hours.

George might just be the perfect client.

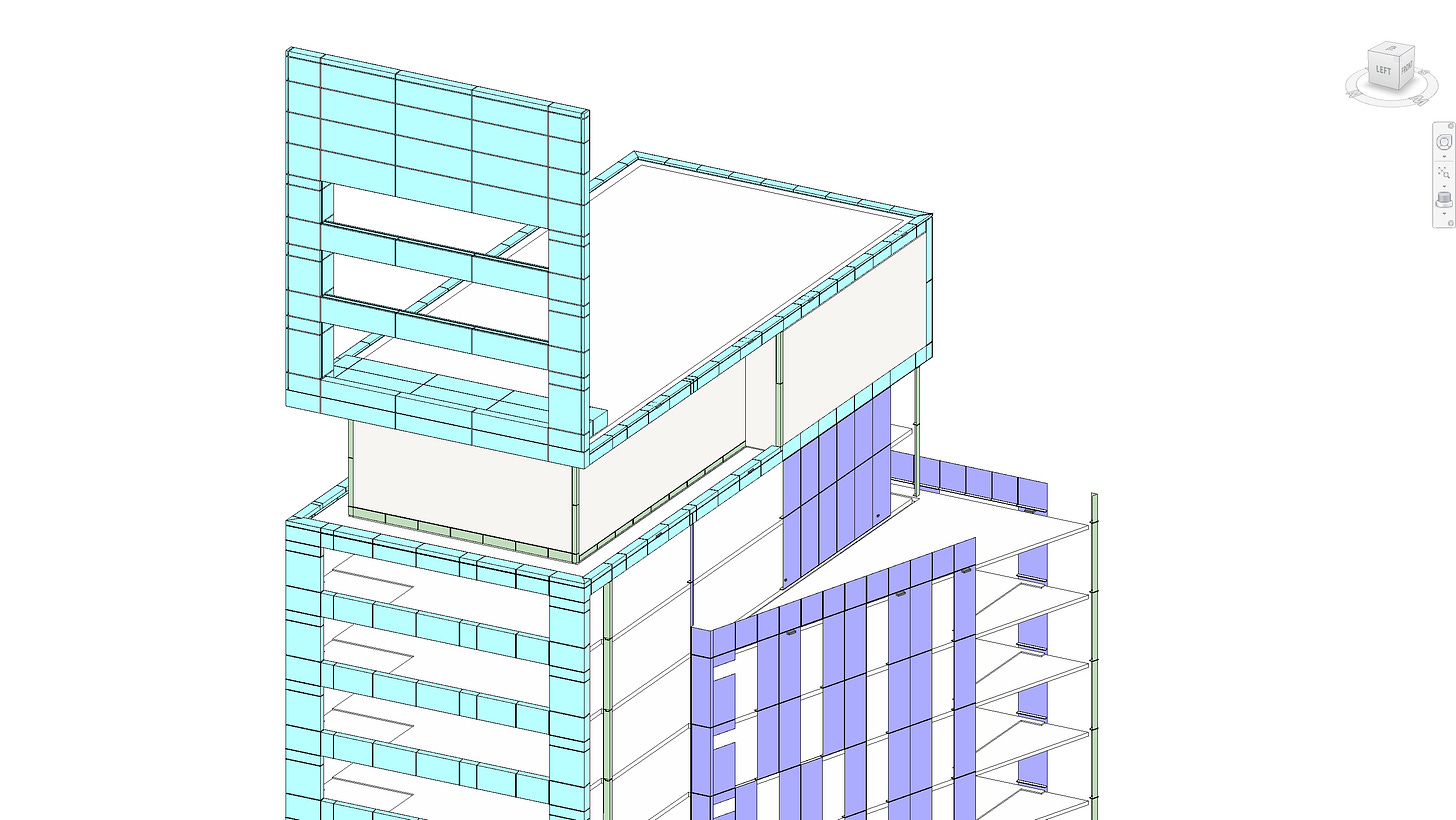

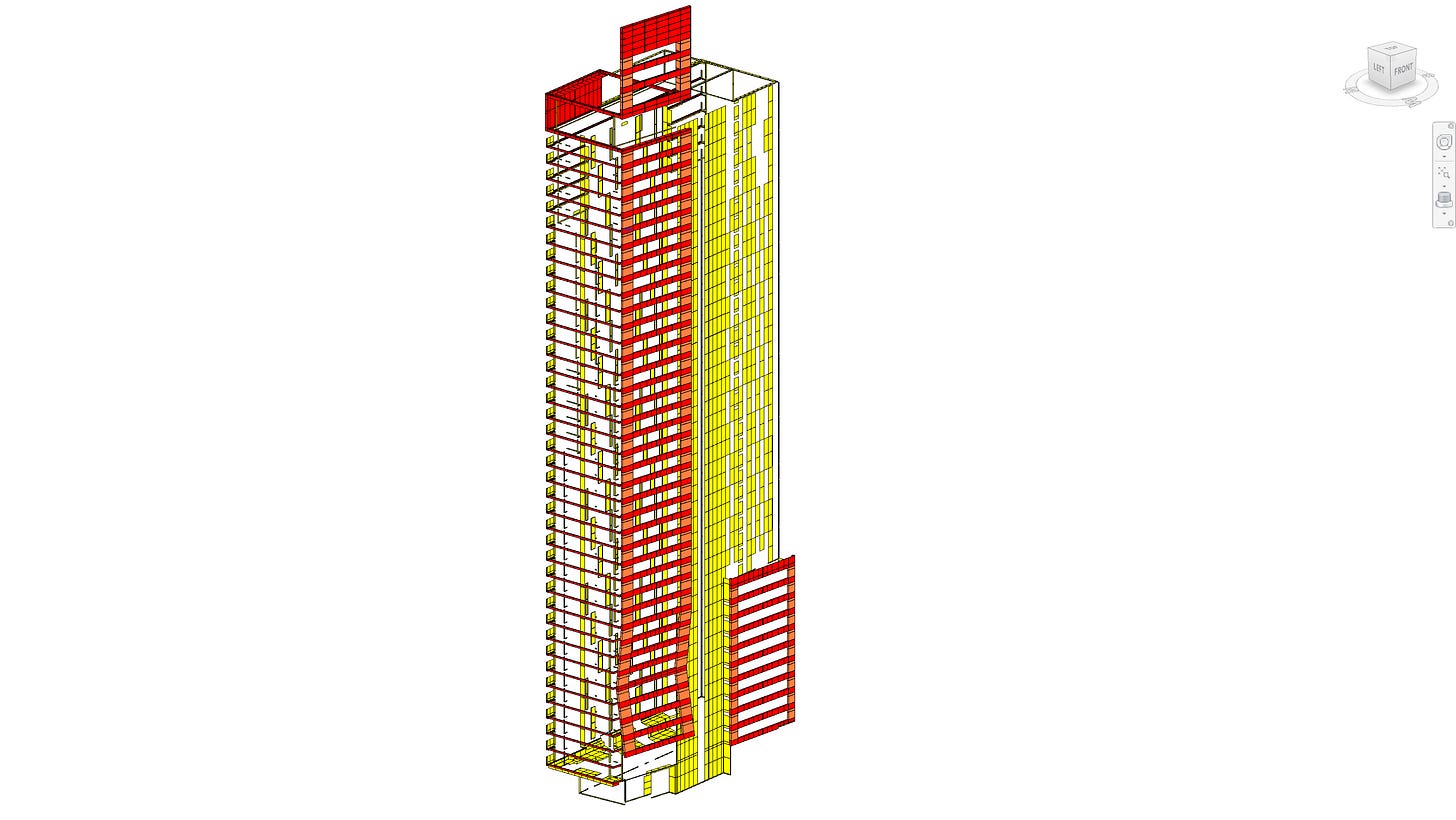

The project also couldn’t have been more perfect. It was updating cladding panels for three towers to meet new fire codes. There were 571 of them. It’s time consuming to place them manually but doing it this through Grasshopper was just a matter of hours. I could create the different panel types and use Grasshopper to systematically place them. It was lucrative for me and low cost for George. The stars really aligned on this one for me.

So, I started work. Setting up the Grasshopper script and within a few more hours, I had some preliminary panels ready.

Then I noticed something odd. Two out of the three towers had some new panels placed in them. Not everywhere, just in small sections of the building.

It was odd. Why am I adding panels in when some of the m have been modelled already. It must be a mistake of some sort.

So I pressed on. Reminding myself to ask George about it on our next call.

But then, there were more problems. Looking through all the models and drawings, I didn’t actually have enough information to complete the modelling. Like how the openings looked like or how many types there were or what to do when panels didn’t have a type.

Then, more problems came. I didn’t have enough information to complete the panels. I didn’t know what the openings looked like. I didn’t even know how many panel types there were.

After a couple more hours, I reached the point where I needed more information from George to continue. That call I had with him went really well, so I am sure this second call will clear everything right up.

So, we hop on a call. At this point, we are about a week into the promised two week deadline for the project.

“Hey George, how are things? Thanks for taking this call, let me show you what I’ve been up to and I have got a couple of questions for you too.”

I screen-shared my progress. I showed him the preliminary panels and even walked him through the high level process of how I modelled them and what was missing. I had missing information but I was really proud of what I’d done.

But George wasn’t his chipper self. He was really quiet actually. Then he replied.

“Alright, it’s cool to see you can model things, but... why are you doing this?”

He then continued: “The agreement was to update the panels based on an ongoing Excel schedule. I gave you the model to test the workflow. I don’t need an updated 3D model, I just need to see their install statuses on the model. It’s one week left into the proposed two weeks, have you only been doing this? I have contractors starting next week and I want to see the statuses of the panels in the model”

Oh. Man.

I replied, “I thought you wanted new models. That was the whole plan. I even wrote in the proposal ‘Update 3D model.’”

George said “Yeah, I thought that meant update the statuses in the 3D model, not create the model itself. I don’t need that. I thought that was clear from our call. You didn’t ask me more questions, so I figured we were on the same page”

Did you ever notice that zoom shows the duration of the meeting in a weird font. 30:03, 30:04, 30:05, 31:03….

I realized that it had been a whole minute before anyone spoke. And George was waiting for me to reply.

My mouth was really dry suddenly. So I attempted to swallow whatever saliva I had and replied: “Okay, I am so sorry about that. I thought I understood you. I didn’t. I jumped to my own conclusion that you needed 3D models. If you don’t mind, can you walk me through what exactly you need?”

George sighed and proceeded to brief me, again. And this time, I made it a point to ask any clarifying questions. Ones that I should have asked from the beginning.

And then I began the real work.

That week, I delayed the two-week project by one week because I didn’t understanding the problem. The call went so well and I was so eager to solve that I misunderstood the entire project. The worst part was that George paid me promptly, gave me the required files, and trusted me.

I damaged that trust by rushing and not understanding.

And now, not only had I wasted a week of time and effort, I had to spend additional time making up for it. What should have been a two-week project became three weeks and George had to delay the installation of the new panels by a week.

Given what happened, George was gracious about it. We corrected course, I didn’t charge him for the wasted week, and I actually delivered what he actually needed in the end.

But that project taught me a huge lesson. One that has shaped my own process when it comes to working with other people. Because the most frustrating part about all of this, is that it was completely preventable. Had I just spend a bit more time understanding what George needed or asking more questions instead of assuming, we wouldn’t be in that mess. (it of course, also taught me to write better and more specific proposals)

As a person that loves the technical stuff, I tend to jump into “solve” mode too quickly. It’s a trend that I see with most computational designers. The tools we have allow us to move fast and there fore we think it’s better to just solve things than talk and plan around them. But planning, understanding and getting the right direction to move is crucial to the success. Even more than the execution sometimes.

This wasn’t the first time I rushed a solution, I have just never done it directly with a client before.

It’s the reason why I have ingrained a discovery phase into my process. If I wasted my time on a bad call that only affected me? That’s frustrating. But wasting your time and money because I was rushing or too eager to solve something? That’s just unacceptable. It’s really about putting in guardrails against my own tendencies to just want to solve things all the time.

How I Make Sure We Build the Right Thing

Don’t get me wrong though, the discovery phase is not about trying to create the perfect conditions to start solving. It’s really about two things: understanding the problem and understanding the dynamics of working with someone new.

As much as I’d love to have a single meeting and a single document to explain all the problems, we normally need a lot more context than that. We have to step back, assess the current landscape of things then decide on how to best move. It doesn’t mean we sit and plan forever, but it does mean slowing down first then moving faster later.

It’s through this process of just “sitting” with the problem that we uncover the real nature of the problem and discover what it’s like to work with each other. I have done this phase with a few teams now, and am constantly surprised by how different the solution ends up being.

This phase is really about getting on the same page about what needs to be done and why.

I know with these things, cost is often a factor and so is the tendency for perfectionism (always wanting more information but never making a move). Which is why many people prefer to just jump straight into solving mode.

But this phase, when done well, is vital towards building the right thing. Experience and pain has taught me that even if circumstances and plan change, I am always grateful for the discovery phase because it gives everyone the clarity to make better decisions when things change, as they inevitably always do.

Good Partnership in Four Phases

Phase 1: Discovery

Okay, we’ve already talked about discovery, but here’s how I operate in this phase.

A lot of times when I speak to other teams, this phase is the biggest push-back I get because they see it as money/time wasted. Or rather it seems luxurious to pause to understand when compared to immediately “solving” the problem.

But as we’ve seen, skipping this phase normally means you’re moving in the wrong direction and that’s costlier than spending that time upfront.

To make this less risky, I typically charge a fixed fee for discovery. That caps the cost while we figure out if automation makes sense. Some teams discover in this phase that automation isn’t worth it and that’s valuable information.

The fixed fee also ensures that we’re not spending too much time planning and understanding without actually moving forward. Even if this cost me more time (and lowers my hourly rate), I find this phase extremely useful for any future work that we do together.

Right, so what actually happens in this phase?

Understanding the status quo

Well, we’ll start with conversations about the pain points, ideas and potentials.

I’ll normally try to get as much detail as quickly as possible. This means screen-sharing sessions, presentations, and just discussions about the pain you are feeling. This is actually the hardest part of the phase because it feels like we are talking a lot but not getting things done. But it’s part of the process.

With George, this would have looked like: “Show me your ideal workflow? How do you envision updating the 3D model”

Those questions would have revealed immediately that he needed visualization, not 3D modeling.

Validating assumptions & workflows

Then with a broader technical understanding, we can drill down into more specifics like constraints or assumptions that you might have but I don’t quite know. Some of it maybe program-related like a reliance on Revit templates that the new solution should also use.

I might start prototyping things, just to show the intended workflow and get feedback on it, to see if we are on the same page. The trick here, is to not jump fully into “solving” model, I generally prototype something just well enough to demonstrate the solution.

With George, a quick prototype that showed how I intended to place the panels would have told me I got the brief wrong. We would have been able to course correct in a day or two instead of wasting the whole week.

Decision point

I then normally summarize all the findings in a little report, so that we have a concrete thing to reference. Some clients don’t go any further because the phase identifies that what they want is either not worth the cost or that they have other problems they need to solve first.

But most of the time, this phase actually drastically changes what the original solution looked like. And we move on to building something that is normally simpler and more focused on the problem at hand.

Phase 2: Build

Now we’re actually building and we’re confident that it’s valuable and impactful. But you don’t just leave it with me and I’ll come back.

As I build out the solution, we’ll keep communicating about everything.

To me, it’s important that everyone involved understands the design process, the decisions that went into it, what it does and what its constraints are. The last thing you want is another black box. Building on the theme of the last phase, it’s all about understanding and clarity.

And as we build the solution together, we’ll also discuss about any problems that we encounter. These are normally problems that only appear once you start building. We’ll also keep testing the solution, to ensure we are always on the same page and that the solution is doing the right thing.

Phase 3: Handover

Finally, I’ll start to transfer the use of the solution over to you. But because you’ve been part of the process the entire time, it’s not a huge leap to understand how to use and maintain the solution.

But during this phase, I’ll start tying up loose ends and preparing some documentation.

Documentation

When it comes to documentation, it’s about two things: how to use the tool and how it works.

Don’t worry, it’s not a 58-page manual that you have to read.

It’s about creating useful documents that can be used as reference when the time comes to actually put the solution into practice. That means documentation written the way you understand it, step-by-step guides on what to click and how things work, and short explanations of how the solution works.

Workshops

Sometimes, I’ll even host longer form workshops with exercises just to get everyone onboard with the solution. This is useful to scale anything we’ve made to a wider group of people.

Phase 4: Hypercare

Okay, but I don’t just hand you something and never speak to you again. I’ll check in and see how the solution is fairing over time. Sometimes I find that things are going well, sometimes there’s some more work to be done to re-align the solution.

Sometimes we’ll extend the existing solution to handle more cases/features because it’s been so useful.

Either way, this is a long-term thing. I’m not just here to give you something and leave, it’s a partnership for a reason.

Final Thoughts

The lesson with George taught me the importance of understanding first and has led me to the current process I use with all teams. It’s built around making sure we’re on the same page before anything gets built.

As someone who loves the technical side, I still have to fight that instinct to jump straight into “solve” mode. But experience (and a few painful mistakes) has shown me that slowing down at the start nearly always pays off later. Discovery, alignment, and clarity are essential to the success of any project.

If you’re thinking about automation or computational design in your own work, you don’t have to adopt my exact process, but I’d encourage you to build some form of discovery into yours. Even a lightweight version, asking a few more questions, mapping the workflow, validating assumptions, can save you from building the wrong thing.

TIf you found this useful, subscribe to CodedShapes.

I’ll send you my free guide on applying computational design at work as a thank you