My Three Biggest Failures in Computational Design

And what their lessons taught me

I’ve been in the computational design field long enough now that I can trace back my entire process to three major failures. It has informed my current process, the way I think about computational design and my stance on all things digital. But as “major” as these failures are, they are, sadly, quite more common. They just vary in severity.

So with the new year here, I’m taking the time to reflect on what these failures have taught me. My hope is you can learn from them without having to pay the same price I did. And at the end, I’ll share the process I use now to avoid repeating them.

Because while I didn’t know it at the time and it definitely didn’t feel good these failures were my greatest teachers.

Failure 1 : Not enough research

Creating a Grasshopper script is often easier than finding the “right” way to do something. So sometimes I skip the research entirely and just open Grasshopper and start building.

Which means there’s a very real chance you end up reinventing the wheel.

And that’s exactly what happened here.

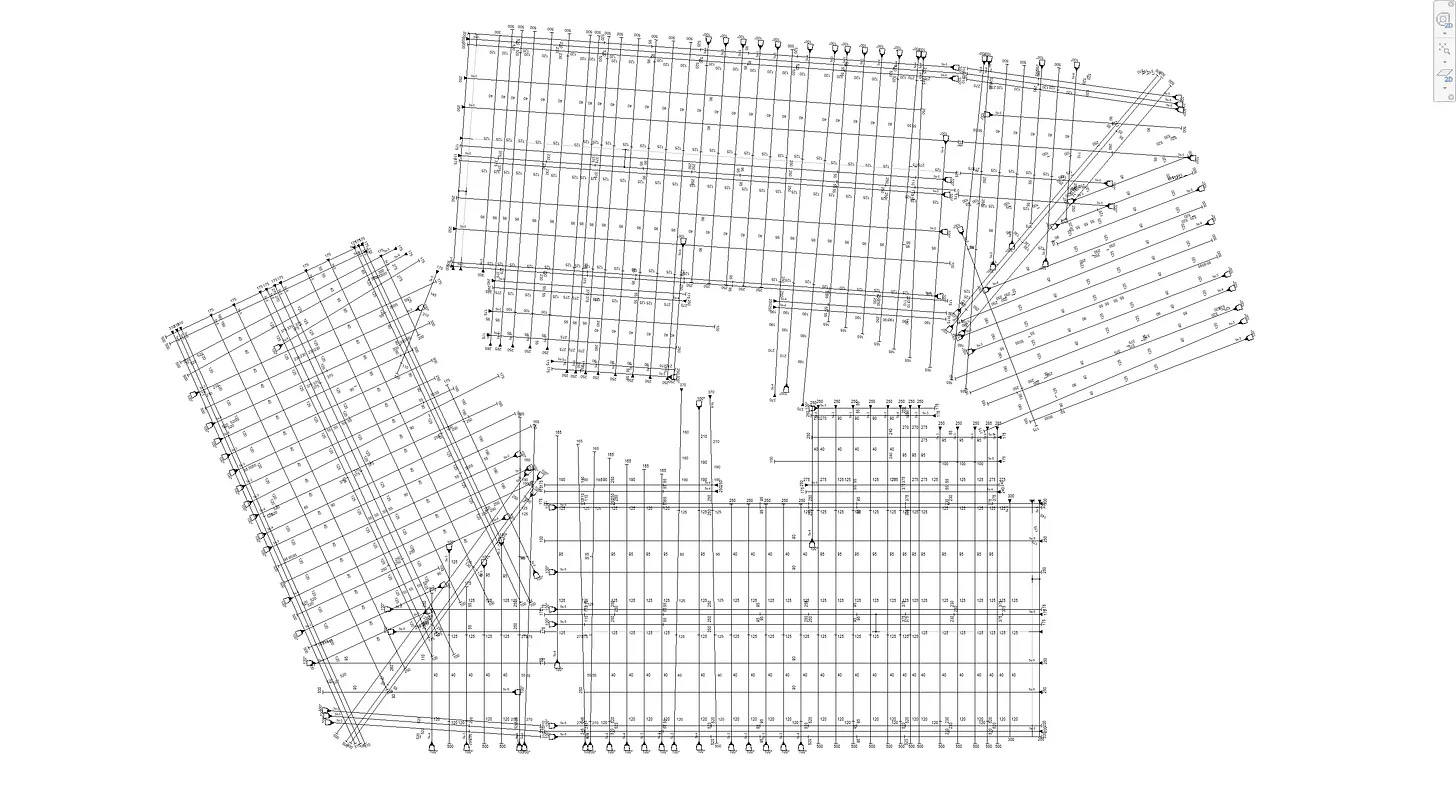

The team wanted to automatically convert post-tension (PT) information from RAM Concept into Revit. Engineers design PT in RAM, drafters model it in Revit. And since they’re nearly identical, automating the conversion made perfect sense instead of manually redrawing everything in another program.

Sav championed this workflow and worked closely with me to get the script running. Once it worked well, we wanted more features. And we because it’s been working well, we got the budget to invest more time.

For the next two months, we added features to the script, ironed out the kinks and even ran tests to ensure everything was still working. It worked so well, that we presented it to other structural teams, hoping for more budget and users. We were genuinely speeding things up.

Then during our presentation, a senior engineer asked: “Why didn’t you just use the export function from RAM?”

I couldn’t answer him. Because I didn’t even know such a function existed. Neither did Sav. I knew what embarrassment was in high school, and well, I was reminded of it again.

The native function wasn’t perfect, but it did 70% of what my script did and was more stable. It would have cut development time in half, maybe more.

I’d just worked on something that didn’t need to exist. All because opening Grasshopper and tinkering was easier than doing the hard work of research.

Two months may not sound like much but when you calculate the cost. It was two months of full time work plus all the back and forth with people plus the testing time for Sav and a few others. It meant that this tool cost about 25,000 AUD to create.

When you compare that against a native function giving you 70% of that functionality for free, it’s an eye-watering amount.

Well, this taught me to always do your research first before building. That there’s a reason why you have to research previous answers before writing a thesis. Because there might already be something out there. Even though building is easier, it’s not necessarily right.

P.S. You might have read about this project before in previous articles like here or here because this project was long and so profound to me that there were many lessons I learnt from it.

Failure 2 : Creating in isolation

The longer you work, the smarter you get. And... well the smarter you are, the more problems you tend to invent.

I was once part of a team with other software developers and computational designers building a new platform. Collectively, we had about 70 years of experience in the industry. We all knew what we were doing. We’d seen the problems and knew this program would solve all of them.

It would unlock so many new and more efficient ways of working. It would solve the manual process of data transfer between all the programs (ETABS, Revit, RAM, etc) once and forever.

It would store and visualize engineering results. No more hunting for files and folders. No more worrying about licenses anymore.

It would show carbon emissions for engineering designs. Manage drawings and documents from clients. The list went on and on.

This was also before LLMs like ChatGPT or Claude, so you can imagine the sheer amount of work we had ahead of us. We were making a web platform together with plugins on all the supported programs like Revit, ETABS, AutoCAD, etc. Again, the 70 years of combined experience gave us a fighting chance.

So, off we went, on our year long conquest to reinvent how people work. We were going to change the world.

It started well. We had regular meetings to delegate and discuss the code architecture. We held several workshops on user workflows. We even hired UI/UX designers for the platform to ensure we had a well designed website to match our impressive logic.

12 months passed and we were ready. We held a presentation to a large group of testers. Mike, our team leader, gave the presentation and organized catering. The entire team went up on stage at the end. It was massive and amazing.

The next day, we checked analytics to see our huge number of users.

We had maybe 20 users. At most.

A year’s worth of work, close to a million dollars spent and we have 20 users.

We had to find out what went wrong. So, we held our first Q&A session after a month.

We were all on stage when the first question came: “Your platform is cool, but how do we actually use it? No one works that way.”

No one knew how to answer that.

The session ended with similar questions that were unanswered. Everyone was confused about how to use it. They thought it was “cool” but not practical.

Our biggest mistake was not working with our users. In that entire year of development, we never once consulted an actual user. We had workflows and dreams of solving problems, but we made all of it up. Our meetings were echo chambers of our own ideas. They weren’t real problems.

We built a program that didn’t align with how people actually work because we built it in isolation.

Failure 3 : No Long Term Support

When I make a script or program for someone now, I don’t just hand over the solution and walk away. I ensure they know how to use it, that it performs well, and I check in regularly. If there are errors or feature requests, I set time aside to implement them.

But that wasn’t always the case.

I’ve shamefully dumped solutions on people and left them to fend for themselves before. What changed everything was the vibration tool I made for Dean a few years ago.

I built a tool that calculated vibration response for models. It worked very well and was constantly used by multiple engineering teams.

Dean came to me with the idea. We worked together for a few weeks developing it. When it was done, Dean told other teams about it. Soon we had more users and feedback than I could handle alone.

But handle them I did.

People reported bugs, they wanted new features, and they wanted to use it on their projects. It felt amazing to create something so useful. I could see the time saved, and people kept praising Dean and me for the tool.

But... and there is a but. Projects that needed this vibration analysis started reducing. That meant that I was no longer working full time on the tool. Requests still came in, but none were urgent. And frankly, there were more interesting problems elsewhere.

So eventually, I stopped supporting the vibration tool entirely. Especially since none of the outstanding tasks seemed urgent.

A few months passed. I was extremely busy on another project when more users suddenly needed the vibration tool again. All those problems that weren’t urgent before, suddenly became urgent.

But, this time I didn’t have time to fix them.

I was frantic, trying to juggle maintaining the vibration tool and the new project simultaneously.

I couldn’t make it work.

The vibration tool kept breaking because I didn’t have bandwidth to support it properly. All the quick fixes I’d put in started failing. Here was a tool, critical to projects, and I couldn’t help.

Being busy and unresponsive, the users gave up and were forced to come up with other ways to do the analysis. Some delayed deadlines. Some manually re-modeled in third-party programs.

When I finally freed up and could to fix those issues, it was too late.

Most didn’t trust me anymore. Even though their manual methods were slower, they could at least solve problems without relying on me.

The vibration tool was eventually retired because no one wanted to use it anymore.

Ever since then, whenever I create a computational solution, I ensure I tie up loose ends and have a system to support people after delivery. It’s never once-off, these solutions need maintenance, and project conditions always change.

People need to trust tools to use them. When people rely on what I make, those tools need to work all the time. Even though it’s unreasonable for me to be available 100% of the time, I make sure solutions are robust and I dedicate time for maintenance.

A Process born from Failures

I’ve made many more mistakes, but these three made my current process for working with people.

The process doesn’t completely prevent mistakes, but it gives me a fighting chance against repeating them. It’s staged to help me shift my mindset depending on the phase, and it has four parts:

Discovery

We work on understanding the problem and explore what a solution might look like. This prevents building the wrong thing and guards against Failure 1.

Build

We build the solution together. No more working on assumptions. I get feedback early and involve everyone to keep things on track. Strong prevention against Failure 2.

Handover

When I hand things over, it’s not just “here’s a script, good luck.” I walk through the solution with you, provide documentation, maybe hold a workshop for any users to ensure we are on the same page.

Hypercare

We go into support mode. You don’t need me full-time anymore, but when changes are needed (errors or new features) I come back to help. We plan in advance what this looks like. It’s about open communication and support when needed. Prevention against Failure 3.

If you want to know how these, I actually go into more depth here

Final Thoughts

Well, I would love to say that ever since I came up with this process, all of these problems just disappeared. But that would be lying.

They don’t disappear just because there is now a process in place.

Even when I first started using it, formalization took time and I had to get used to working this way. I still get tempted to skip discovery when something’s exciting, or skip documentation because I think the solution is “self-explanatory.” But these phases remind me to slow down instead of jumping from problem to solution.

They help me build things properly.

Want to learn where to apply computational design?

Subscribe to CodedShapes and I’ll send you my free guide on how to actually do that