It's an engineer. It's a Drafter. No, Wait ...... it's...

The role that fits everywhere and nowhere all at once

You know, I love computational design.

Every day looks different. The problems are weird and interesting. And the best part is I get to experience a little of everyone's world. One day I am helping out the Structural team with Excel, the next I'm modelling a complex 3D model for finite elements analysis. Next month will be some Revit plugin development.

That's the magic of it. And it's what keeps me in the field. We're always solving interesting problems and making that impact. But sometimes I wonder if that same diversity is also holding us back?

We’re the ones who know a little bit of everyone’s world. Just enough engineering to work with engineers. Just enough drafting to work with drafters. Just enough architecture to talk shop with architects. But not quite enough to be any of them.

We’re too engineer-ey for drafters. Too draft-ey for engineers. Too something else for anyone. We’re the glue. The digital glue. We speak everyone’s language just well enough to connect the dots. But like most glue, we’re often invisible.

That can be… frustrating.

It's gotten better now. The world has advanced and people have more terms to help describe us now. "Digital Engineering", "Technologists", "Automation Engineer", etc. All close, but none quite fit. Even "computational designer" still feels a bit off but it's the best fit right now.

What sets this field apart is how dependent we are on others. Computational design doesn’t exist alone. It’s always in service of another field. It's always about helping people better leverage computers. In that sense, we’re closer to conventional software developers than most realize.

Despite the confusion (and the constant need to explain what I do), I love this work. You get to see the whole problem, not just the little slice that belongs to one team. You connect disciplines. You fix gaps. You solve problems no one even realizes exist — until they’re gone.

But that's actually my biggest worry. Because we don’t sit neatly in any one discipline, we don’t fit cleanly into traditional roles. Most computational designers I know are hybrids. Structural engineer and Grasshopper user. Drafter and Dynamo user. All because we still need to tether ourselves to an “accepted” job title.

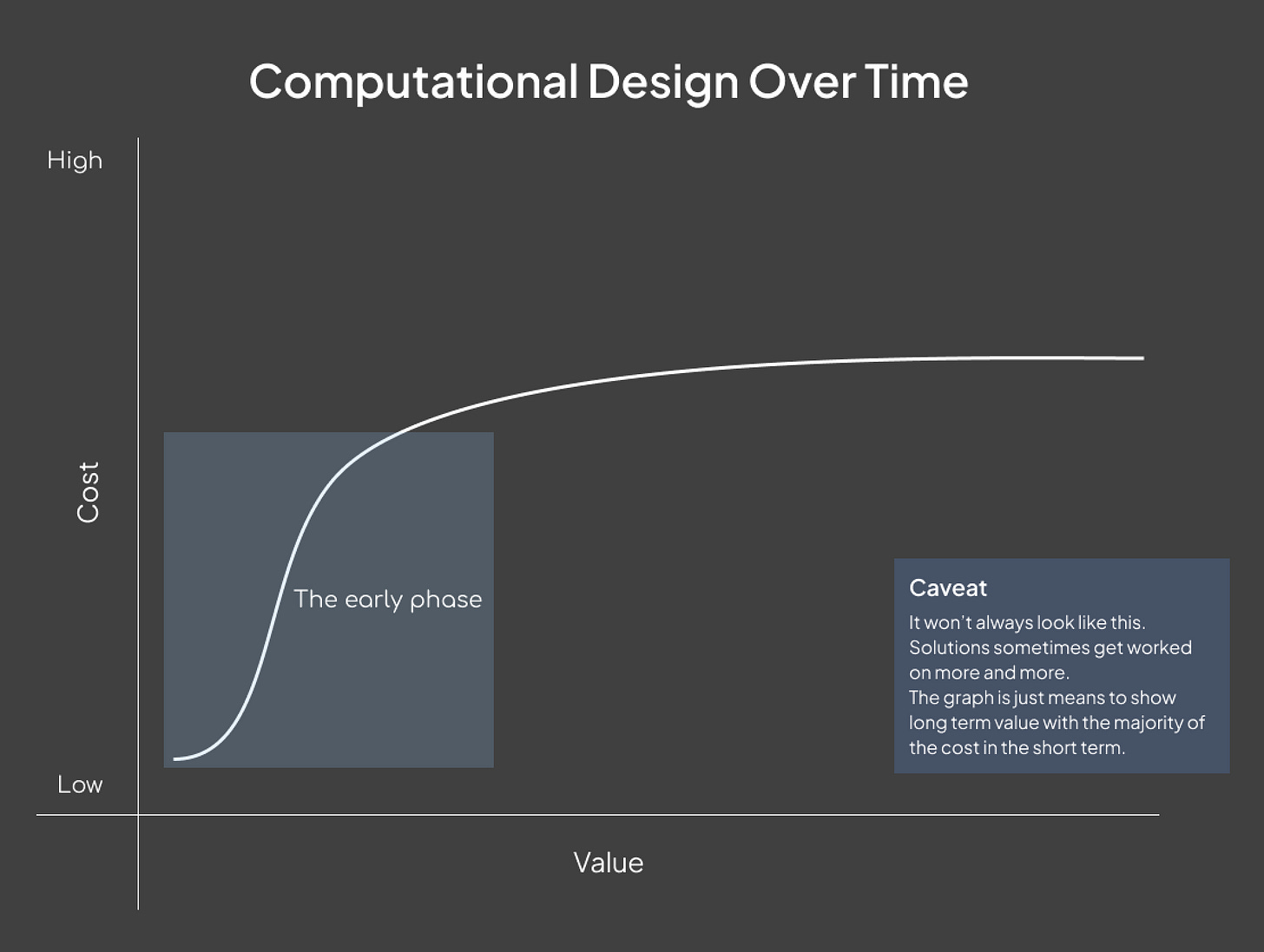

When our success depends on others, it's harder to justify our value, especially in businesses with tight margins. How do you measure something like “enabling better workflows across teams”? Most companies fall back on a simple metric: time saved vs. time spent.

That’s a tough metric for long-term impact.

What if I spend three weeks building a tool, and that tool quietly saves time on hundreds of projects after? That kind of value doesn’t show up on the next invoice. It shows up slowly, over months or years. But most companies only measure what’s directly visible.

I don't actually blame companies for this. It's hard to tie metrics to our value. It's actually closer to R&D than traditional project work.

The problem then is the uncertainty of our value. How do you measure our value? Is it time spent on projects? Time saved for other teams? Number of tools delivered? All of these are flawed metrics and yet we’re often judged by them.

It reminds me of software teams. They’ve figured this out. Developers aren’t tied to project budgets, they’re part of a larger, ongoing investment. But with tools like Grasshopper and Dynamo, we can directly contribute to projects. And once companies see that, it becomes the only thing they ask of us.

But that misses the point.

We can do more than project work. We see everything and that perspective lets us solve problems across teams and projects. But those solutions don’t fit neatly into a project box. They’re harder to bill. Harder to track. Easier to cut.

Not All Doom and Gloom

This isn’t a pity article. It’s not all doom and gloom.

We’re not some underappreciated geniuses waiting to be discovered. Like any field, we just need to find the right fit: the right company, the right problems, the right collaborators.

The good news is that things are changing. I’ve seen it. More teams and clients recognize the value we bring. More companies are investing in internal capabilities. There are even computational design consultants now which are still tied to an industry. But it’s a start.

I’ve been tempted to leave for full-time software roles. But I can’t. The problems here are just too damn interesting. The complexity. The messiness. The human-ness of it all. It matters. And I care about it deeply.

If there’s one thing I’d tell a younger me — or anyone new to computational design — it’s this:

Doing the work isn’t enough, you have to communicate it

And yes, I get it. The work is already hard. Explaining it is even harder. But if we want computational design to thrive, we can’t skip that part. We have to get better at telling the story. Better at showing the value. Better at getting people to understand what it is we do.

Because it's all part of being early, at least that is what I tell myself (having started this Substack, posting on LinkedIn and Youtube).

It’s awkward. It’s weird. But it's also exciting. Remember the first vloggers? The first time you saw someone talk to a camera in public? That's us. We’re early. The world doesn’t quite know what to call us yet.

But they will.

Until then, we keep building. Keep experimenting. Keep sharing. Because that’s how we earn our seat at the table, not just by solving problems, but by helping others see the problems we solve.

Want to learn where to apply computational design?

Subscribe to CodedShapes and I’ll send you my free guide on how to actually do that