Cool Features Won't Save Your Computational Design Tool

Understanding your users will

We were in our weekly team meeting when Maria brought up an idea for a new tool.

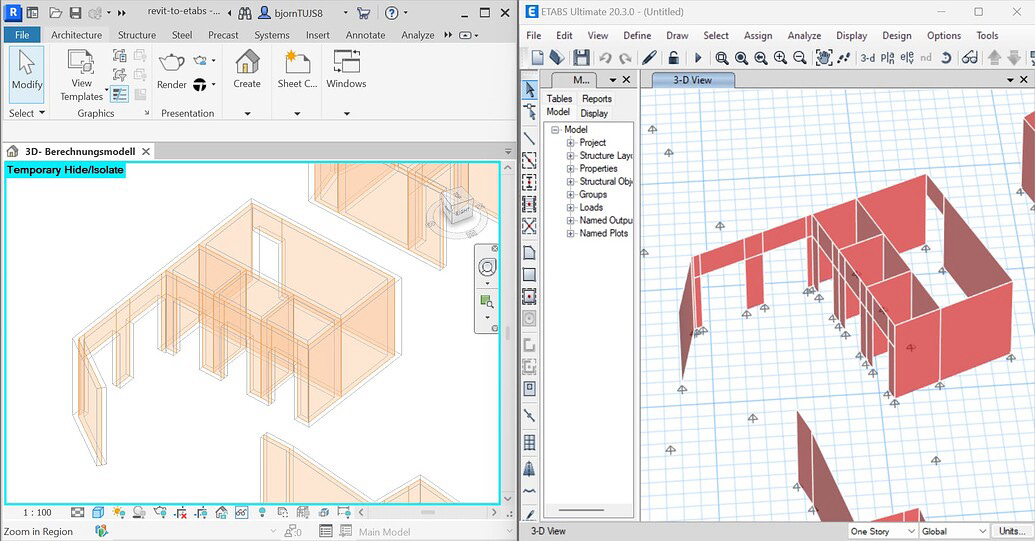

"I have an idea for a tool to convert Revit models into ETABS models", she said

For context: Revit and ETABS are used for very different things. Revit is about documentation, ETABS is about structural analysis. Converting one into the other isn't just about moving the geometry, it's about understanding what each model has to do.

The entire team (including me) was skeptical. We'd all tried to solve this problem before. Actually, everyone in computational design at some point has a built a script to convert a Revit model for a project.

It's a hard problem. Revit models vary wildly in quality. And ETABS models need to capture the engineering intent, not just the geometry. They are very different use cases.

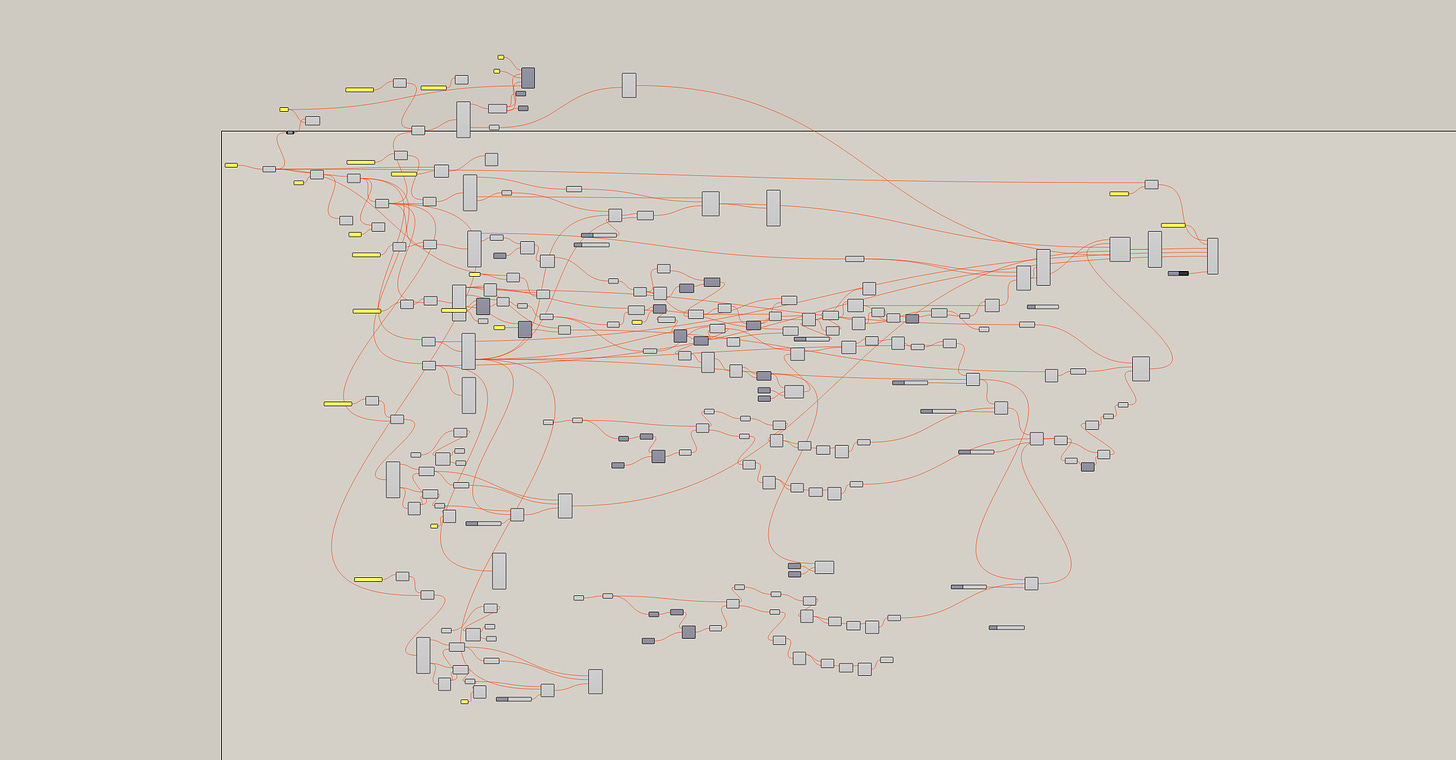

But despite our skepticism, Maria continued her pitch with full of optimism. She kept it grounded and knew that a 100% conversion was not possible. Her idea was to create a set of custom Grasshopper plugins to do at least 70% of the conversion and have engineers clean the rest.

She wanted to create a set of modular Grasshopper components with some template scripts to do the conversion.

The team lead was sold. He gave Maria the green light to explore further and prototype the tool.

P.S. Get my free guide on how to apply computational design at your work here.

The Build

A week later, Maria reported her progress to the team. She showed us a Grasshopper script that did the conversion. It was looking good. As she spun the model in front of us, we were getting excited. Soon, the entire team started throwing in ideas.

Break the walls at the floors. The columns should snap to the grids. The tool should automatically draw beams on the edges of the floors.

These were ideas we’d all had for years but never acted on it. Now, with a working prototype in front of us, it felt possible. I pitched in too, suggesting ways of handling the data structure and the interaction between the components.

Maria may have started it but now the entire team was involved and working on it.

Two months later, we had a working script that would convert a few models. We even tested it on some past projects and were impressed with the results. We even showed the models to a few engineers and they couldn't believe that it was done automatically.

Everything was going better than planned. A problem that had frustrated people for years suddenly looked solvable.

So, we decided to go big on the release. We scheduled a big lunch time presentation. We scheduled four workshops. We even got in touch with the marketing team to write an email blast showcasing the tool. We were changing lives and we wanted everyone to know.

Deployment

We were excited. We were confident. We were also completely wrong.

Our script was a big hit. Everyone wanted to try it, all 634 of them.

Well…. it was a Grasshopper script with a custom plugin, not some fully developed program. So, getting it to work on everyone's computer was difficult. Not everyone had the right version of the tool installed. Not everyone knew what Grassshopper was. Not everyone had Rhino installed.

And, to make matters worse, not every model worked. When we tested the script, we only tried a handful of models and they were all buildings. It turns out an ETABS model for a train station is very different to an ETABS model for a tower.

Also, not every model relies on grids and not every model needs beams on floors.

It was a disaster.

People had to install new software, learn a new workflow, and still deal with broken models. It costs them more time and frustration to use the tool than to just manually convert the models. In the end, no one wanted to use it and everyone hated it.

It was months of wasted effort.

What Went Wrong

We didn’t talk to engineers about what they needed. We didn’t ask if they were happy using Grasshopper. We just assumed. Every “feature” was based on our own wish list, not on what they actually needed.

Even though we had brainstorming sessions, we only ever did it within the team. We were an echo chamber that fantasized on how people should be using the tool. But reality doesn't work like that.

We should have put in more time and effort into understanding what the problem actually was. We should have spoken to more people and get a more diverse set of opinions before we poured months of development time into it.

Even though this was about 3 years ago, it still happens every now and then. We get so caught up with the tools, the features, that we forget about the people behind the tools.

"Won't it be cool if it did this?". Well, it'd be cool if people actually wanted that.

Walking the line

It's a tricky situation because we can't build exactly what people ask for either. Most of the time, they don't know what's possible or what they are truly after. Our job as computational designers is to dig deeper. To listen, ask questions, and uncover the real pain points before we even think about code.

It doesn’t mean we agree to every request. But it does mean grounding our ideas in reality. Not in our own fantasies. It does mean listening to people more and using their ideas and feedback to guide what we build.

It's actually why I wrote this article as an argument that computational designers should operate more like consultants. We need to source ideas and solutions from people but use our instincts, skills to filter them and guide what we do.

Final Thoughts

So, before you start building anything, it’s worth setting aside some time to talk to the people you’re building for. Understand how they work, what slows them down, what they’d be happy to change, and what they’d never give up.

If you started building something, test your assumptions. Walk people through what you are currently building. Ensure that they are onboard with the workflow and what the solution is doing.

Because the hardest part of computational design isn’t just the implementation, it’s also building something that people will actually use.

Want to learn where to apply computational design?

Subscribe to CodedShapes and I’ll send you my free guide on how to actually do that