Computational Design isn't Magic

So let's stop treating it like it is

Mark was angry. But that's normal, at least for Mark. What's new is him marching towards me. Something must’ve gone wrong on his project. Still, why he was walking towards me ?

"This is the last time I will be yelled at by the client!", he shouted as he got nearer and nearer. "We've missed three deadlines and I look like a fool in every meeting". He started "explaining" the problem before he even reached my desk.

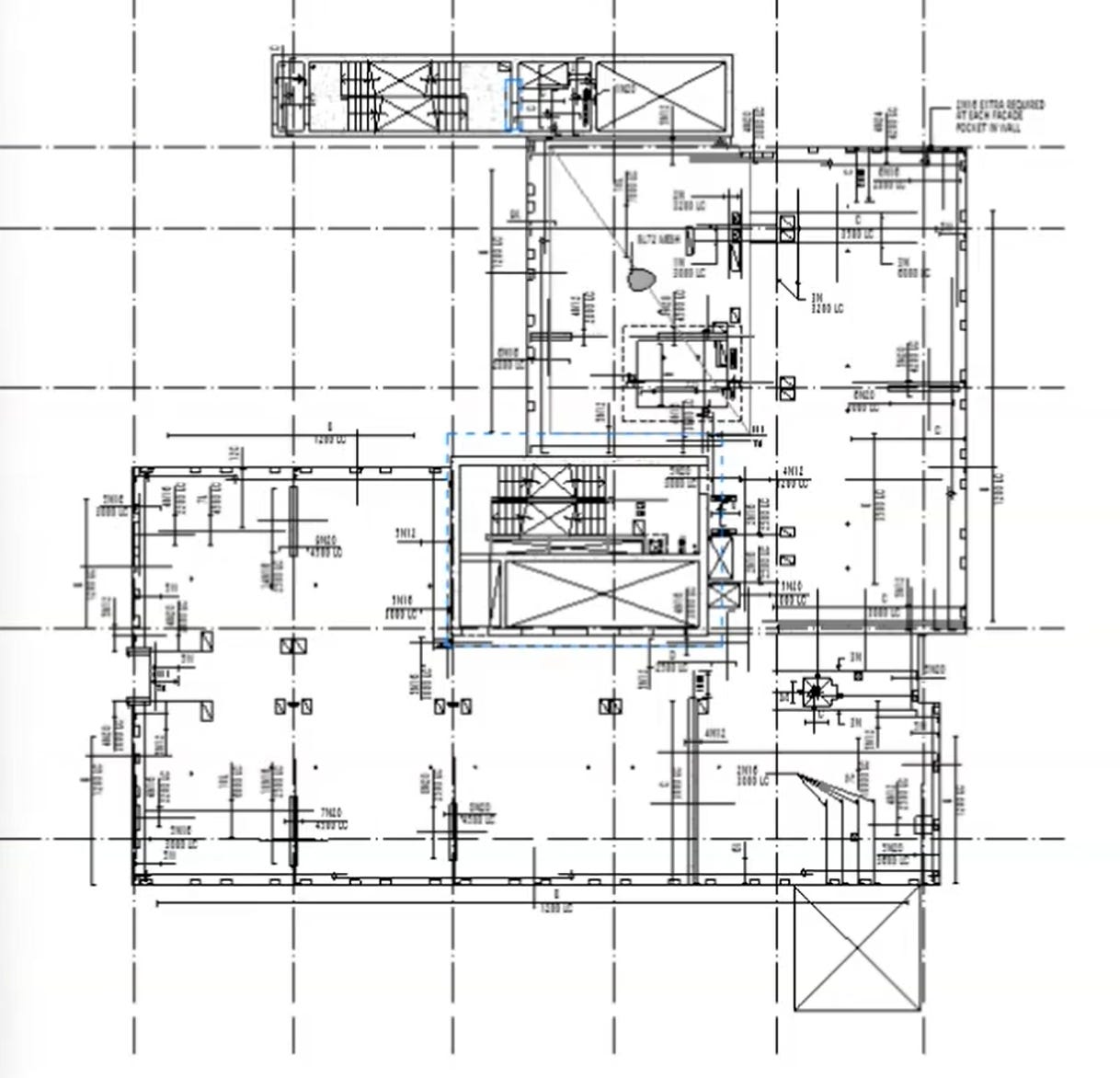

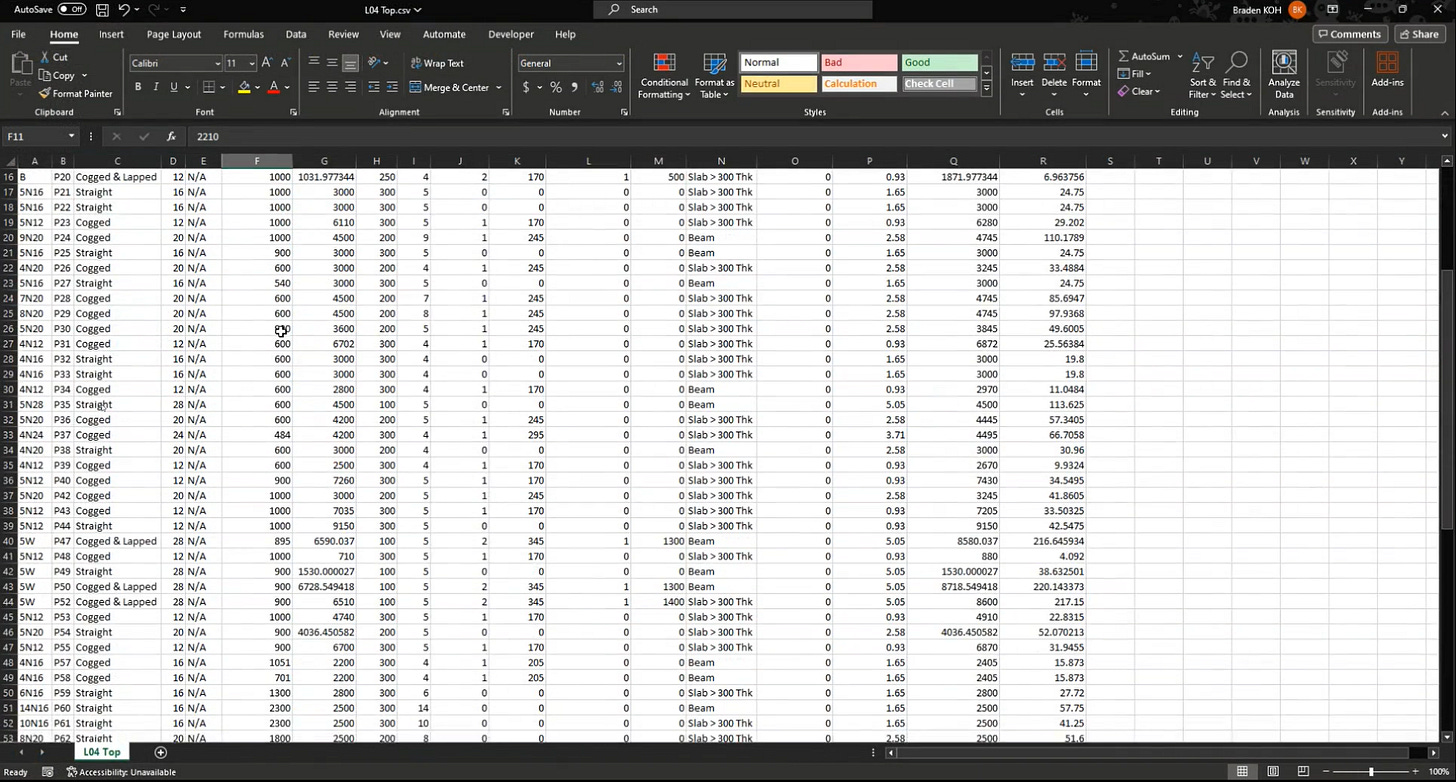

Through Mark's very loud voice, I learnt that the engineers on his project were manually counting reinforcement bars (rebar) on each floor. Counting one floor could take up to a day. The tower had 36, which meant every time something changed, it took at least one week to deliver the numbers to the client. Even then, the numbers were not always accurate.

Mark had enough. "You're a good with computers. Come up with something", he said, already marching back from where he came from.

I had a bad feeling about it but I agreed because the project clearly needed help. And well, I also felt bad for the engineers stuck counting rebar under the deadline (and Mark's tyranny).

When Mark was no longer in sight, Nat leaned back in her chair and said, “Well… I guess we’ll finish our chat later. Seems like you have a new deadline” We were mid-conversation when Mark began his one-man performance.

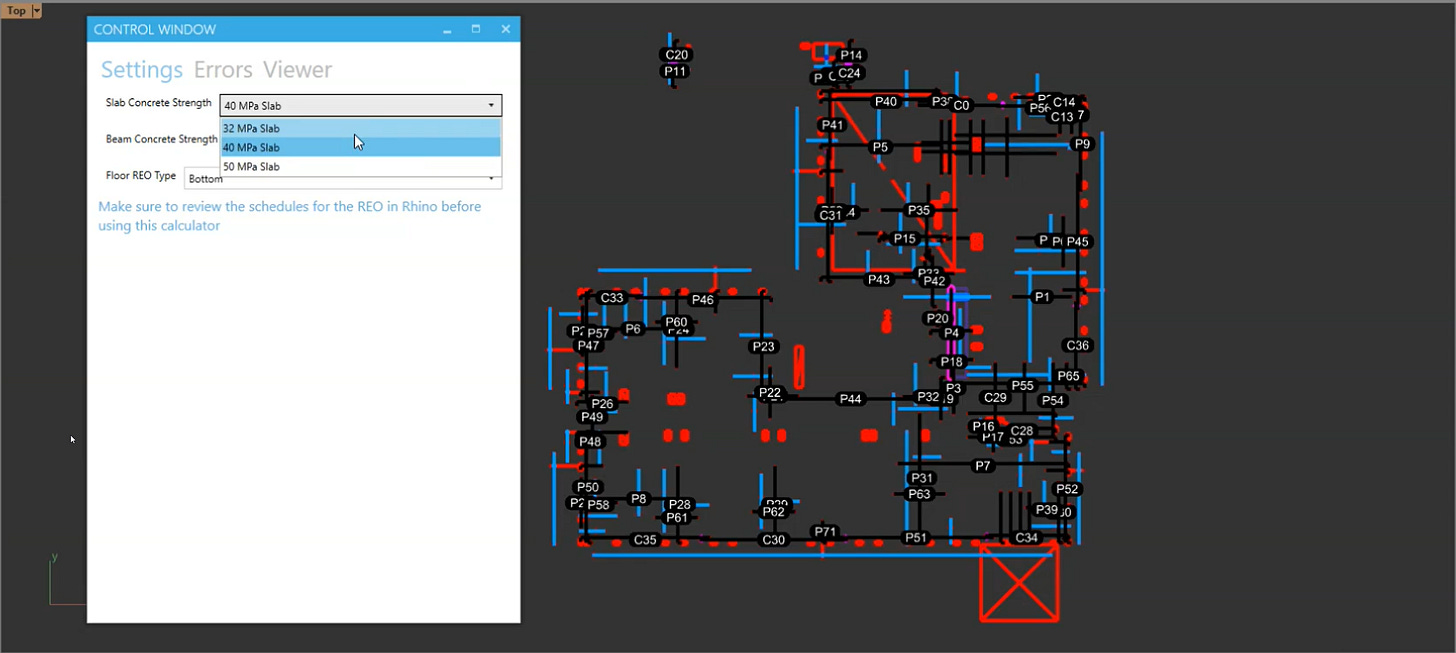

So over the next week, I sat with a few engineers on the project to understand what's really going on. Then, I started on building a tool to help count rebars automatically.

Tom, one of the engineers on the project, already understood the basics of computational design. I’ve worked with him a couple months ago on building his own computational tool. He was good. He pinpointed the core problem and even pitched a few ideas on how this rebar counting tool should work.

We stayed late every night that week, including the weekends building this tool. While I was building, Tom reviewed the logic, flagged issues, and told me about all the weird edge cases in the model. All while still doing his normal job.

That week felt like one long day, but we got a working version out. After testing it on a few floors, Tom showed the team how to use it.

Over the next few weeks, I checked in regularly with Tom. The team loved the tool. It was working exactly as designed. What used to take a week now took 30 minutes. They even asked for more features, which is usually a good sign.

It was rushed. It should’ve been part of the plan from the start. But at least with this tool, they were back on schedule.

About three months later, Mark came storming over again. I guessed the tool had worked so well that he had a new problem he wanted me to solve.

I was wrong.

"The tool you built is useless. It's quick but gives us the wrong numbers. I just got yelled at by the client again.". His voice was louder this time.

I told him that I'd take a look.

“Don’t bother,” he said. “The engineers fixed your mistakes.” Then he left before I got a chance to understand what was going on.

I wasn't too bothered....

Okay, I was. I mean who wouldn't be? No likes getting yelled at. But I knew the tool was doing the right thing, it was pulling quantities straight from the floor plan. I was confident and proud of my work but I knew I needed to find the problem.

So I went to speak to Tom. Turns out the drawings were wrongly drafted. He meant to tell me earlier but he had just been too busy. Some bars had been duplicated in the model, which caused a miscount. The tool did exactly what it was told to do, the inputs were just wrong. Deleting the duplicated bars in the model solved the problem.

I thought that was the end. There was an issue with the inputs, it was fixed and the project is running smoothly again. But the next day, my manager Alex pulled me into his office. Mark was already there, looking like he'd been waiting awhile.

“Mark says computational design is a waste of time,” Alex began. “That it didn’t save the project and it isn’t worth the company’s money.” Mark just standing there looking down at me.

I explained the situation. The tool was accurate. The drawings weren’t. I reminded them (especially Mark) that I was brought in last-minute, and that we rushed to get something working. I didn’t stop there.

I continued to explain that computational design isn’t magic. You can’t pull it out only when things are on fire and expect miracles. It needs the same things as any design process: time, context, and constraints.

Just like you wouldn’t ask an engineer to design a high-rise in a week. You can't expect computational design to produce miracles instantly. Anything useful and impactful needs to be well thought out.

Alex just looked at Mark. Mark’s smile vanish but he knew he couldn’t say anything to change the situation.

“Well, next time we just get you in earlier,” he said, and walked out. Alex, expressionless just shrugged.

The Messiness of Computational Design

People think the hardest part of computational design is the coding or the Grasshopper scripts. It's not. It's actually getting in early enough to setup critical workflows for the project.

Okay.... getting tools to work on other computers is hard too but that's a story for another time.

By the time I was brought onto this project, everything was locked in. It was too late to rethink the process. And too late to build something properly. There’s no space to test, adjust, or even ask the right questions. There’s just the pressure to deliver something.

All I could do was write a script on top and hope it didn’t break.

That’s what a lot of people get wrong about computational design. They think it’s a shortcut or some magic bullet. For computational design to actually help, it needs to be treated like any other part of the process. It needs to be planned and incorporated early on.

But I get that it's hard to do. We don’t look like a “real” part of the team. We’re not drafters. We’re not engineers. So, it makes our work harder to explain or quantify and easier to leave out. But that needs to change if we ever want to maximize the value of computational design and I believe there is a lot there.

Computational design isn’t magic. It’s not the magical elixir that will save you when nothing else works. It’s still design, and it still needs time and planning.

If you want it to work, you have to make space for it.

I’ve seen what it can do. But that only happens when it’s given the chance to do the work properly.

Thanks for reading. If you’ve enjoyed that, consider subscribing.

When you do, you’ll get a free guide on how to apply computational design to your own work