5 Questions That Made Me Rethink Computational Design

I'm writing this from my hometown in Malaysia, far from my usual desk in Sydney. Being back home means two things, quality time with family and indulging on way too much food. Something about food back home just hits differently. The kind that makes you realize how much you've missed home.

It's week 2 out of 4 weeks of a total disconnect from anything computational design related. I do this every year as a soft reset and to have the space to step back and think about how I can be more helpful to everyone else.

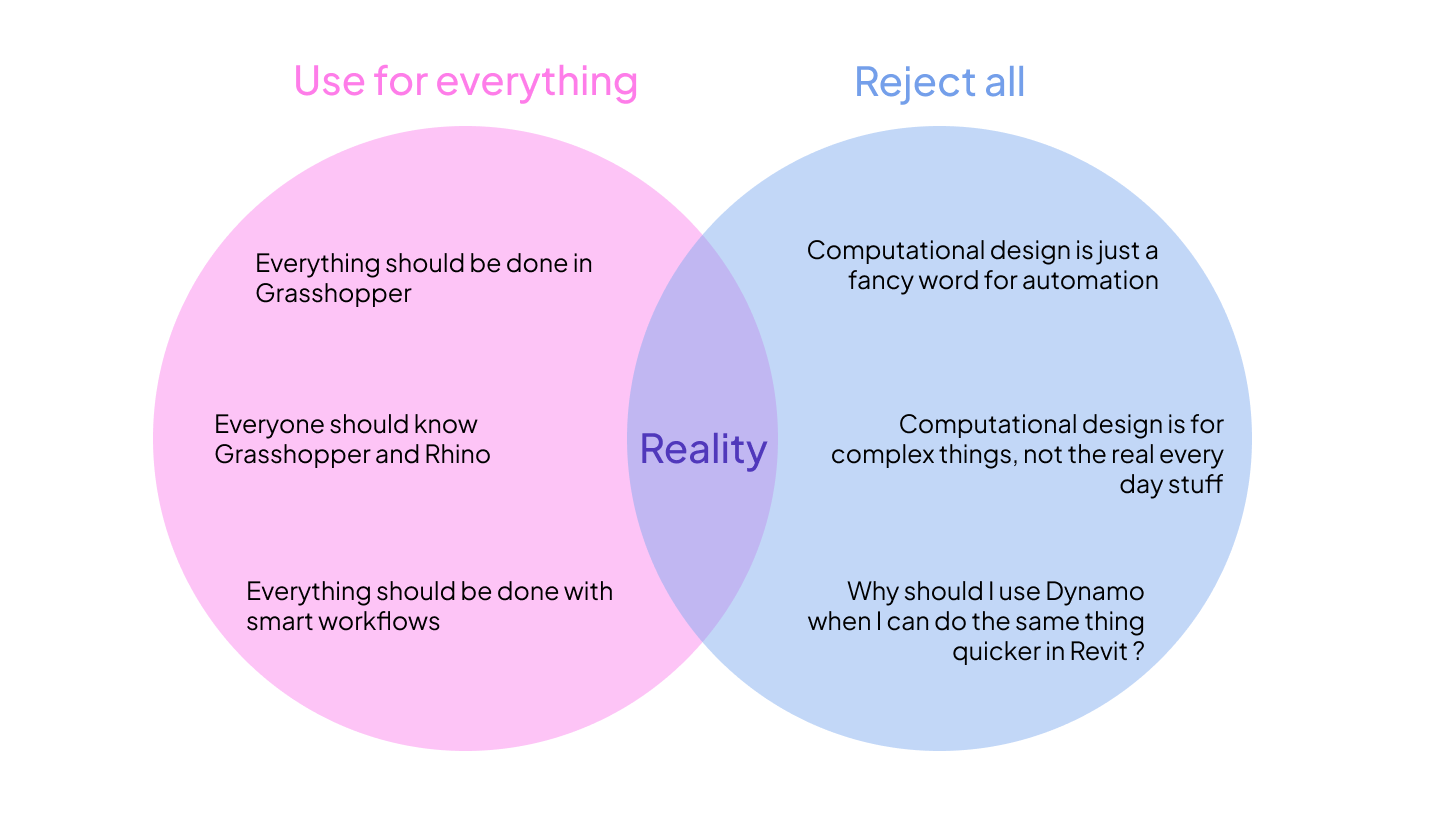

One thing that keeps coming up in my mind is how we talk about computational design. If you do a brief scroll through LinkedIn, you'll start to notice that there are largely two camps around the field. Those who want to use computational design for everything (and I mean everything), and those who reject it entirely.

I've flickered between both camps at different points in my career. Right now, I seem to leaning towards the "don't use it if it isn't going to be helpful" mindset. The truth, like most things in life, lies somewhere between these two camps. It's made me wonder if we there is a way to help us see if computational design is the right fit for any given problem or situation.

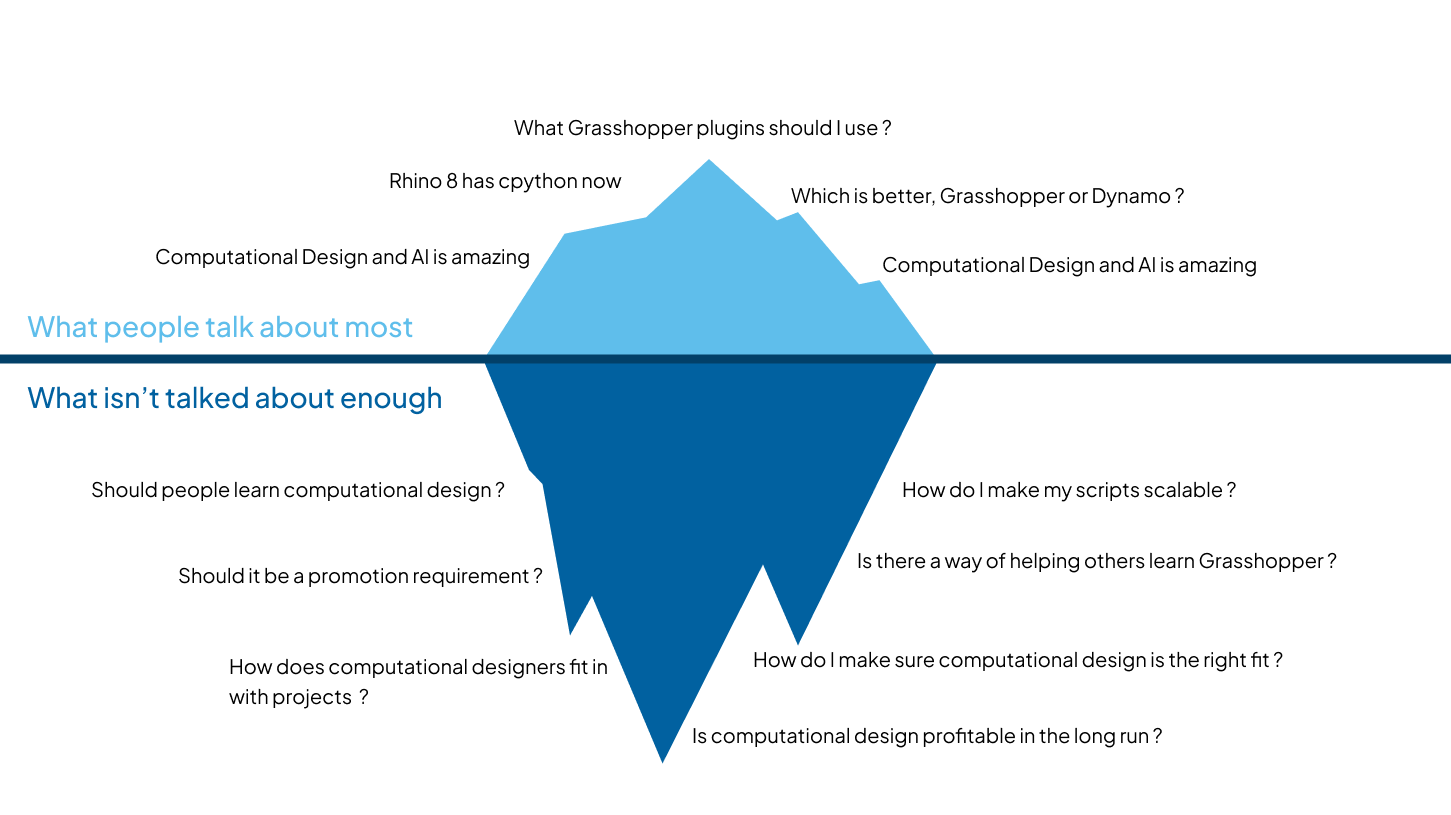

What might help bridge these two camps is changing the way we talk about computational design. Many of us (myself included) mostly talk about the tools and processes that drive efficiency. I can actually go on for hours about how you should use data trees in Grasshopper. But the biggest problems I've encountered in my work aren't technical at all, they're human problems.

Things like how do you communicate your value, how to scale solutions across teams, or even just getting people excited about trying something new. All of which aren't unique to computational design. They're the same challenges that are in every field. Yet somehow, they get way less airtime than the latest Grasshopper technique because it isn't as flashy to talk about.

So as we head into 2025, I want to share five questions that have changed how I approach my work. These are helpful reminders that help me consider the human and more operational side of computational design. They help ensure I don't get too tunnel vision about only solving the technical challenges.

1. "What Problem Am I Actually Trying to Solve?"

This one hit me hard early in my career. Anyone could come to me with an idea and I would just dive in right away. No further questions asked. Then, I go into "work mode" for a month, deliver the solution, only to be met with "I didn't ask for this, now you've wasted half our budget".

When a problem first arrives at your desk, it's most likely incomplete. You will be missing the many details that you need to actually solve the problem. Even though it's from a good intention, most people have trouble communicating the exactness of their problems.

This normally leads to the wrong thing being built and a lot of wasted time. It's a two sided problem. We get so excited to do the work that we don't stop and consider the actual problem and the other people don't communicate their problems very well.

To help combat this, I've since learned to pause and really think about what I'm getting into. Am I writing a quick script to save someone a few hours, or am I potentially rebuilding how an entire team works?

It's really about putting in that upfront work to understand the problem, so that you're always solving the right thing.

2. "Who's Actually Going to Use This?"

Unless we are building just for ourselves (which is rare), we need to think about who's going to use our work. I've made some beautiful solutions that took me months to make only to realize that I was the only one that could use it.

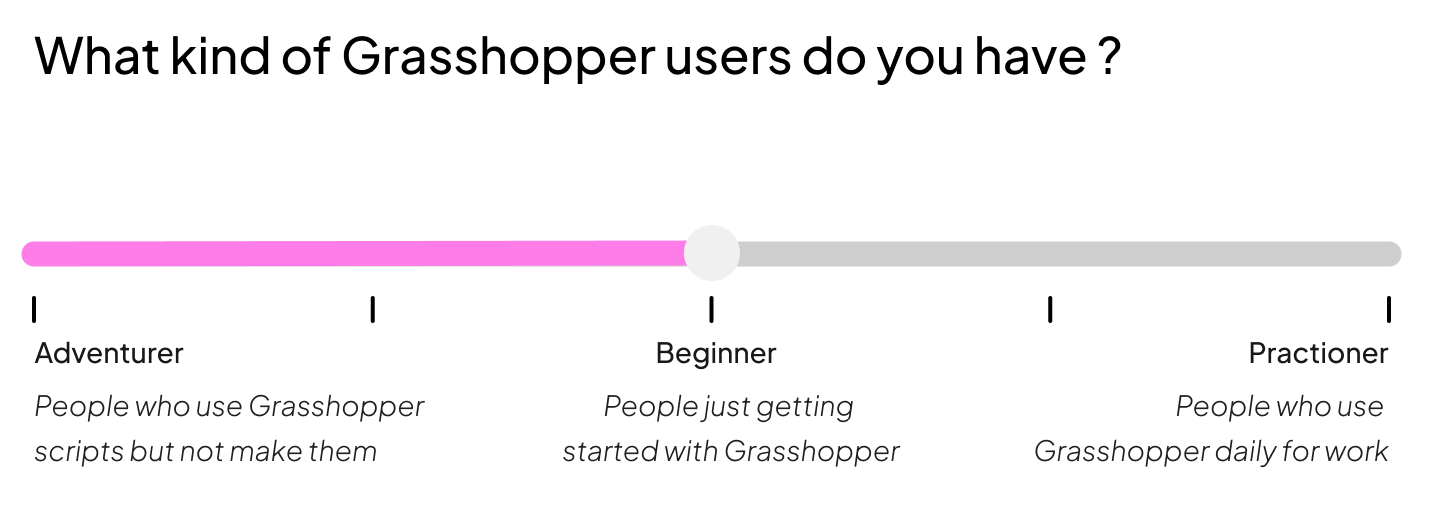

It's easy to forget about the humans on the other side. We fall into this trap of thinking that everyone is like us. That everyone is smart enough to figure out how to use the things we've built. That assumption is almost always wrong.

I am not saying people are dumb but it's about shifting the focus to the actual users of our work. If you're building a Grasshopper script for someone, pause and think about how user friendly it actually is. Does your users have experience with Grasshopper ? Do they even know how to open the file or how the program works ? Depending on your users, you might have to change the how they interact with your work.

Questions like these might sound simple but they can heavily influence the scope of work you have to do. Adding a separate user interface on top of a Grasshopper script can easily double it's size and complexity.

By always thinking about the user, you can be sure that whatever you built remains useful. It's the reason why there is a whole industry (UI/UX) dedicated to thinking about users. There is no point in building something amazing if people can't use it.

3. "Can This Solution Last?"

Here's something we don't talk about enough: maintenance. I used to treat every script or tool as a "one and done" deal. Write it, hand it over, move on to the next exciting thing. But that's not how it works in reality. Everything we make becomes something that we have to maintain.

The more complicated it is, the more effort it takes to keep it running smoothly. I've seen amazing tools get abandoned simply because nobody thought about who would maintain them. The people that made them leave the company and there is no documentation, so the tool just gets put in the discard pile.

Every time you build something, it's worth thinking about how and who will maintain it. Who's going to update this when things change? How will we make sure everyone has the latest version? Is there room in the budget and time for someone to maintain this ?

4. "Do We Really Need This?"

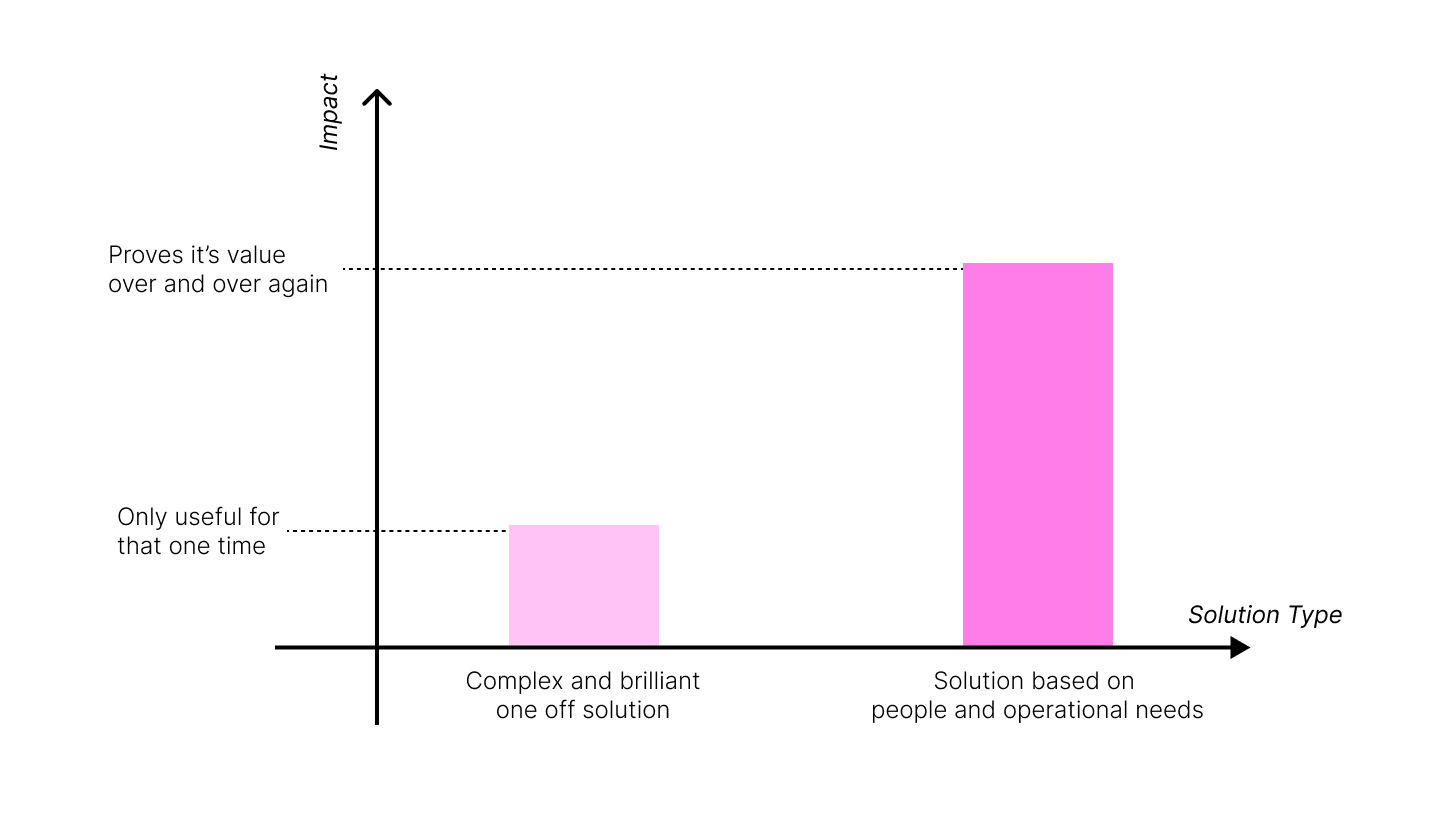

This is a tough one, especially if you're like me and get excited about helping people. Just because we can help doesn't always mean we should. As computational designers, we get exposed to a lot of tools out there, not just Grasshopper. It emboldens us to build and solve anything and everything. It's an awesome skillset to have but not every problem needs to be solved.

As much as I like to keep solving interesting and hard problems, it should always come down to the priorities and urgencies. The true skill is understanding which problems are truly worth our time and effort.

Most ideas or problems usually come from one of two places: either we spot a pattern and think "I could automate that" or someone comes to us with a specific request. These ideas although they come from a good place aren't usually field tested. You don't actually know if it will be helpful to everyone of not. Unless the director of the company is telling you to do it, then you should just do it without asking (I'm joking, it's always worth asking if people really need what you're building).

You will never run out of ideas and problems, the real skill is being able to tell which ones are important.

5. "Could This Fix a Bigger Problem?"

A unique thing about computational design is that we sit at the intersection of a lot of industries. This gives us the privilege of noticing big picture patterns that others might miss.

This insight means we might be able to build something that solves a common problem across all domains. Before working on the next problem, it's worth pausing to think if there is a similar solution that you've made for someone else before. Does it follow the same logic or flow ? Does it only require a small tweak for it to work for everyone ?

This might actually mean more work, but you create something bigger and more valuable that just solving one problem. Things like Speckle or IFC were created because these people noticed a larger scale problem to be solved amongst everyone.

Looking Back, Looking Forward

These questions have become my mental checklist. They've helped me create solutions that actually stick around and make a difference, rather than just adding to the clutter. They help ensure that what I am working on will be impactful to the people around me.

The most effective solutions I've created weren't necessarily the most technically impressive. They were the ones where I took the time to understand the real needs, consider the human element, and think about the long-term impact.

As we move into 2025, I hope these questions help you as much as they've helped me. They might just save you from building something nobody needs, or better yet, guide you toward creating something that really makes a difference.

Want to learn where to apply computational design?

Subscribe to CodedShapes and I’ll send you my free guide on how to actually do that